Chronicles of Cecil Beaton encounters, costume balls, social events leaving behind the diary and photographic records of his trips

Fashion Eye Venice by Cecil Beaton in Venice: the city of St. Mark’s lion

Dark water as greenish as the pane of an ancient mirror. Or water the color of jade and pale blue. Rippled by tiny regular waves as in the eighteenth century paintings by Canaletto and Marieschi. A score of almost geometrical waves with gentle white foam in the St. Mark basin and facing the turquoise space of the Giudecca Canal.

Along the network of canals large and small, in squares with the remote and abandoned air of Piranesi ruins; there is a sequence of palazzos with elaborate gothic embellishments that defy gravity and common sense. Resting on ogival porticos or merely perched on improbable pillars.

Sometimes there is a well-curb at the center of these open-air rooms; while the arched portal supported by the fluted columns of a Renaissance church invites us to enter into the inviting soft shadows smelling of mold and cold, extinguished incense.

The boundaries of reality expand, change color and dazzle, multiplying and blurring the rit- ual of encounters and coincidence. More than Vivaldi, once the curtain of darkness falls, one thinks of Mozart’s Così fan tutte, the bittersweet and melancholic marivaudage of the Rosenkavalier.

And the already post-modern metric composition of Igor Stravin- sky’s The Rake’s Progress, which premiered at the Fenice Opera house on September 11, 1951. A week after the last epochal Twentieth Century Ball held at Palazzo Labia by Charlie de Beistegui to celebrate the glorious twilight of the Ancien Régime.

The ‘Ball of the Century’ in Venice, on September 3, 1951

Nothing could seem further from this era of snobbishness as art, and the movement towards boundless sophistication pursued by a Franco-Mexican gentleman between the 1930s and 1960s. Carlos de Beiste- gui y de Yturbe was born in 1895 and last seen in 1970.

He was a patron of avant-garde art from Bauhaus to Cubism and Surrealism. His rooftop attic over the Champs-Elysées conceived by Le Corbusier in 1929. Later an interpreter of baroque splendor and of the last courts of the ancien regime. Charlie – as his many friends called him – specialized in worldliness. He did not have a count’s title. With endless waves of money and a refined education, he collected houses, personalities and artistic splendor.

Europe emerged from the horrors of the Second World War. That was the Venetian home of Charlie de Beistegui until 1964. Palazzo Labia, a classicist Baroque building, built for a family of Catalan merchants who became Venetian patricians ‘for the money’ on the Canal of Cannaregio in San Geremia.

The Venetian home of Charlie de Beistegui

It’s an aristocratic residence which is now Venice’s RAI headquarters. Frescoed with the Stories of Antonio and Cleopatra by Giambattista Tiepolo at the height of his career, 1746- 47. There were thousands of guests: three hundred more than planned.

For the most part immortalized by Cecil Beaton, Cornell Capa and Robert Doisneau. Among them were members of the high aristocracy and Café Society of Europe. There were the Aga Khan III in black domino; Orson Welles, Gene Tierney and Irene Dunn in lace and tricorn; Elsa Maxwell; the Hollywood gossip; the procession of imperial chinoise by Lopez Willshaw and Alexis de Redé; Daisy Fellowes; Barbara Hutton. Famous for her many husbands, and Isabelle Colonna, Fulco di Verdura, Natalie Paley, Duff and Diana Cooper, relying on Oliver Messel’s costume design.

Elsa Schiaparelli, Nina Ricci and the young Pierre Cardin were among the costume designers. As was Jacques Fath, who participated in the Louis XIV gold celebration; to depict the sun, accompanied by his wife in lunar silver. Salva- dor Dalí was there with Leonor Fini, the black angel of Surrealism. The landlord, who walked on a forty centimeter plateau, wore a scarlet damask toga; as a procurator of the Venetian Republic with a Louis XIV wig.

Sir Cecil Walter Hardy Beaton and Kodak 3A

Through his early photographs Beaton documented and experienced the full range of entertainment of the Bright Young Things; the generation that experienced its youth between the two world wars in the 1930s, characterized by carefreeness. Sir Cecil Walter Hardy Beaton – his housekeeper introduced him to photography with her Kodak 3A, a popular model at the time.

She also taught him how to develop his photographs. He often used his mother and sisters as models. When he had sufficiently mastered his craft, he sent his photographs to society magazines using a pseudonym. Beaton entered Harrow School and soon afterwards St John’s College, Cambridge, where he studied history, art and architecture.

Beaton continued with photography, and through his university connections was able to take a portrait of the Duchess of Amalfi, published in Vogue. It was actually George (Dadie) Rylands – «in a slightly blurred shot of him as Webster’s Duchess of Amalfi in an underwater light outside the men’s room at the ADC Theatre in Cambridge».

Cecil Beaton career in photography

Beaton left Cambridge without a degree in 1925. Beginning his career photographing his wealthy hedonist friends in Bright Young Things, he also worked with the fashion magazine Harper’s Bazaar and as a photog- rapher for Vanity Fair. In 1930s Hollywood, he took many celebrity portraits and was the official portraitist for the Royal Family in 1937.

Henry James, in his disquiet Aspern Papers, describes Venice as a collective apartment, while Gabriele D’Annunzio in The Flame transformed it into a labyrinth of passions and opulence.

Here Marcel Proust was enthralled by the Byzantine gold of Saint Mark’s and the textile reinterpretations of Mariano Fortuny as much as by those sunrises and sunsets on the lagoon that had already seduced Joseph Mallord William Turner. Tonal intervals between light and darkness caressed by a mist reflecting Tiepolo-like sunrays.

Cecil Beaton encounter with Donatella Kechler

Henry James used to write in the library on the second floor of Palazzo Barbaro, residence of his friends Curtis, Bostonians who had decided to settle in the nineteenth-century Serenissima. Isabella Stewart Gardner also passed through here, seeking inspiration for her Fenway Court.

The gothic residence near Ponte dell’Accademia on the San Vidal side hides a triumphant salon of white and gold baroque stuccoes, the work of Abbondio Stazio. The paintings by Giambattista Tiepolo were removed and the rich art collections of one of the most important families of the ancient Republic, traditionally linked, through the patriarchate of Aquileia, to the papal court, dissolved.

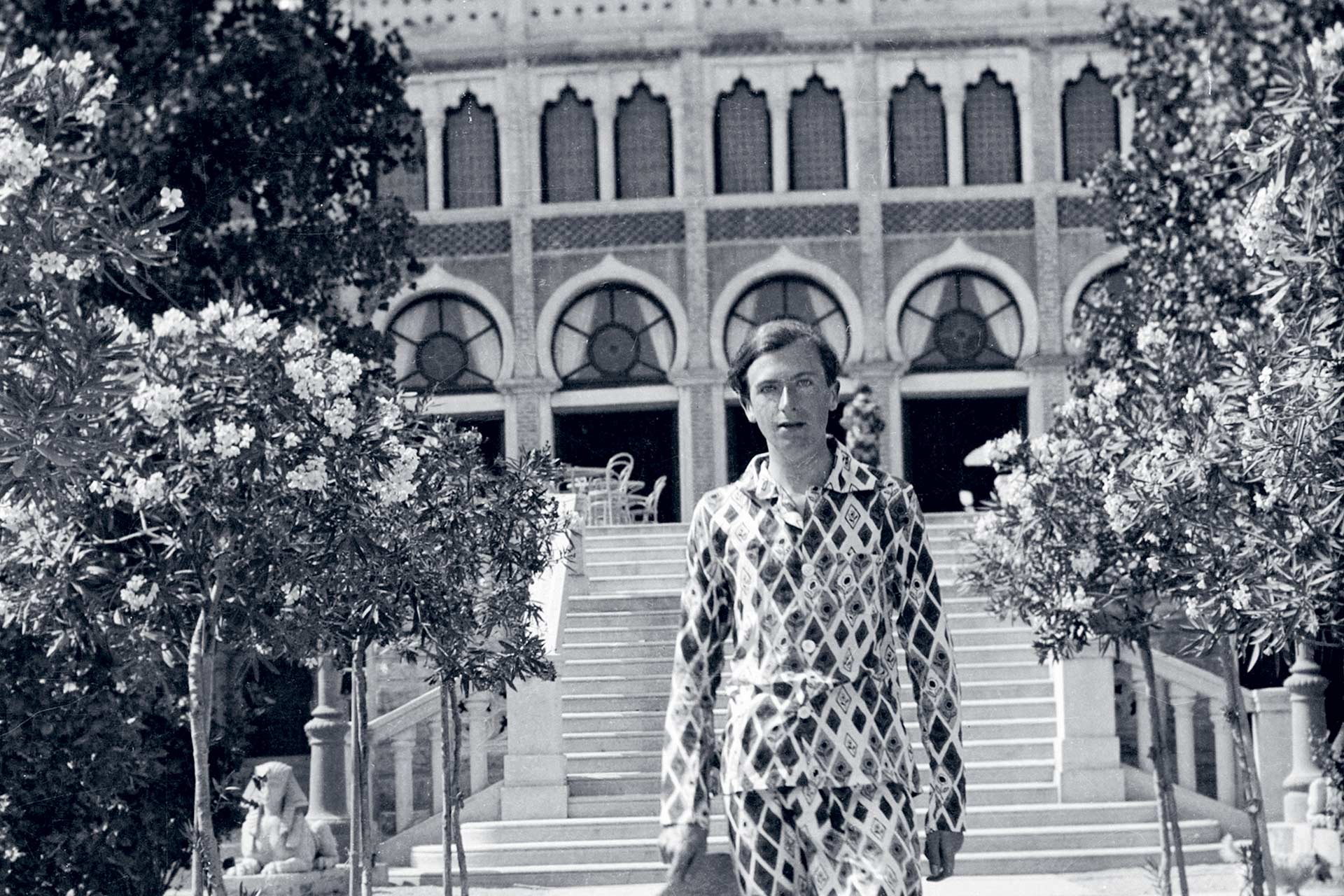

An array of eighteenth-century rooms adorned with a subdued and elegant décor; now houses the floating and transparent geometries of Laura de Santillana’s glass. An anecdote. In the late Fifties Cecil Beaton was a guest of Brando Brandolini d’Adda, in Venice. Count Brandolini was the husband of Cristiana Agnelli – one of the very few partecipant still alive of the Bestegui ball.

He saw by chance a little girl in the street, and asked her if he could photograph her. He had no idea who she was. Donatella Kechler, a Friulian countess with an androgynous beauty, married to Paolo Asta. She was for a long time among the Venetian socialites and beauties at Palazzo Mocenigo de Cá Nova. More times her name appears in the International Best Dressed list. Her parents – in particular her father Alberto – were friends of Hemingway. The portrait seems to be that of a Hellenistic head or a heraldic and suspended Donatello. The eyes are distant and deep as the sea.

The Byzantine-Venetian architectural grammar

Venice – the city of St. Mark’s lion with origins shrouded in mystery and a fish-like morphology; the outpost and gateway to the East – only reveals itself to those who surrender to it, who decide to lose themselves in it. Venice was an extension of Byzantium that imposed Saint Theodorus upon it; as its patron saint until the Republic of Venice; finally liberated and the remains of St. Mark were removed from Alexandria after a rocambolesque theft.

Cardinal Bessarione considered Venice to be the third Rome and bequeathed to the city his prodigious library. A treasure trove with classical roots and millennial wisdom that was rescued during the fall of Constantinople and saved from the greed of the Borgias. Gothic Venice, embracing its arches, was devoted to the inversion of building volumes entrusted to slender supports rising from the water as the only possible language.

The humanistic winds blowing from Central Italy arrived late on the Lagoon and were looked upon with suspicion and caution. The subversive weight that wove the message pondered and dissected. The Renaissance verbum therefore struggled to be accepted; initially relied on the idioms of compromise of the Lombards and Codussi. Focused on interpretations of the Byzantine-Venetian architectural grammar based on a nuanced, archaic and solemn coloring of stone.

Palladio’s grandiloquent idea for rebuilding the Rialto Bridge

The candid and heroic delirium of Palladian geometries and colonnades burst onto the scene. However, Palladio’s grandiloquent idea for rebuilding the Rialto Bridge burned by the latest fire was rejected by the Venetian Signoria as being too ‘Roman’ for the Serenissima.

Especially after the crucial defeat at Agnadello on May 14, 1509; when the apocalypse seemed to manifest itself on that battlefield between Bergamo and Crema; and abruptly stopped any further expansionist aims of the Republic on the mainland. The brilliant Andrea was therefore rejected for a simple Proto; who had a more modest and restrained vision compared to his Olympic apotheosis; compared to a Walhalla with haughty and chillingly classical design.

It was too superb. Baroque means Baldassarre Longhena, who, with the Chiesa della Salute, left his mark on the tip of the Dorsoduro quarter, thrown like an arrow into the basin of St. Mark’s. The overloaded and narra- tive facade of San Moise by Alessandro Tremignon is Baroque. A theatrical setting dominating Calle Larga XXII Marzo, one of those great streets created during Austrian rule that greatly changed the face of the Serenissima, encroaching upon its distinctly aqueous character.

The illusionist ceiling fresco by Louis Dorigny flows in the main hall of Ca’ Zenobio – where part of the Like a Virgin video was shot in 1984 starring a young Madonna – and materializes in the huge chiaroscuro painting by Alessandro Fumiani that covers the ceiling of the San Pantalon church.

Water, an ambiguous and elusive element itself

In this baroque plot there has to be Fornimento Venier. A crazy suite of chairs, ebony moors, Rococo consoles and gueridon pedestal tables; forty sculptures created by Antonio Brustolon for the Venier family of San Vio between 1680 and 1703. Today the pride of the Museum of Eighteenth Century Venice in Ca ‘Rezzonico, designed by Longhena and completed by Giorgio Massari.

This was precisely where Cole Porter in the early 1930s composed the musicals Anything Goes and Jubilee. The unforgettable ballad Begin the Beguine. It was here that he welcomed Chanel and the Robilants, Boris Kochno and Fulco di Verdura, or elegantly seduced, under the clear eyes of his wife Linda. Handsome gondoliers and local firefighters, with great scorn of the fascist police.

«Times have changed. And we’ve often rewound the clock». Yet it is always water, an ambiguous and elusive element itself that is even more difficult and mysterious to decipher in its duplicity of being both lagoon and sea; which is the turning point of this magical and fluctuating overworld called Venice.

Campo San Stefano, one of the largest squares

With a monument to Niccolò Tommaseo at its center which the Venetians prosaically call ‘cagalibri’ (book-pooper), stands the massive, majestic Palazzo Pisani. The residence was owned by an illustrious patrician family that through its various family lines distinguished itself in the eighteenth century by commissioning architectural and artistic works in the lagoon and on the mainland.

One example is Villa Pisani in Stra with its park and the ceiling of the main hall frescoed by Giambattista Tiepolo During the Napoleonic era, he became the viceroy residence of Eugène de Beauharnais. Ca’ Pisani had a bizarre destiny, stretched out as it is; courtyard after courtyard; loggia after loggia; looking for a front-row view of the Grand Canal.

This interruption, the castration of a yearning experienced as fateful project and symbolic mission, is still felt as a powerful element, as something that is slightly unsettling and has remained unresolved, a tension that declares a kind of impotence – and it does not matter if the desired destination was finally reached through the enclitic of Palazzetto Pisani, children of a lesser God, a lovely pygmy with a giant behind it.

The story of Ca’ Pisani

Ca’ Pisani never got its space right on the Grand Canal; regardless of the political power and wealth of its owners; it had to grow vertically, right up to a huge terrace that sees and controls everything; soaring above a quagmire of roofs, domes and bell towers. For generations it has been the home of the Benedetto Marcello Music Conservatory. This maze of rooms, staircases, vaulted ceilings, open spaces and dizzying depths echoes with voices and musical chords, orchestra rehears- als and piano solos.

The story of Ca’ Pisani in San Stefano is long and complex. Initially a former seventeenth-century factory trans- formed by Girolamo Frigimelica into a patrician residence in the eighteenth century; it was later divided into apartments before becoming the music conservatory. The celebrated collections of paintings owned by the noble family. And the huge library full of heretical texts no longer exist.

However there are still rooms with eighteenth-century stucco work by Giuseppe Ferrari, doors inlaid with ivory, mother of pearl and tortoiseshell, chapels and elegant salons now devoid of furnishings. What was once the ballroom, completed for Almorò Pisani between 1717 and 1720, is now used for concerts. The ceiling was decorated with a painting by Antonio Pellegrini which was sold in 1895 and replaced in 1904 by a work of Emanuele Bressanin called The Glorification of Music.

Fashion Eye Venice by Cecil Beaton

Edited by Patrick Remi, 2021, Louis Vuitton Publishing. After Louis Vuitton City Guides and Travel Books, the Louis Vuitton Fashion Eye collection evokes cities, regions or countries through the eyes of fashion photographers. Cecil Beaton (1904-1980) left photographic records of his trips to Venice – costume balls, swimming, social events, traditional festivities.