A military driven mission allowed for an unnecessary production of ignorance of our oceans during the Cold War period – we now face the problems of years of negligence

Science on a Mission

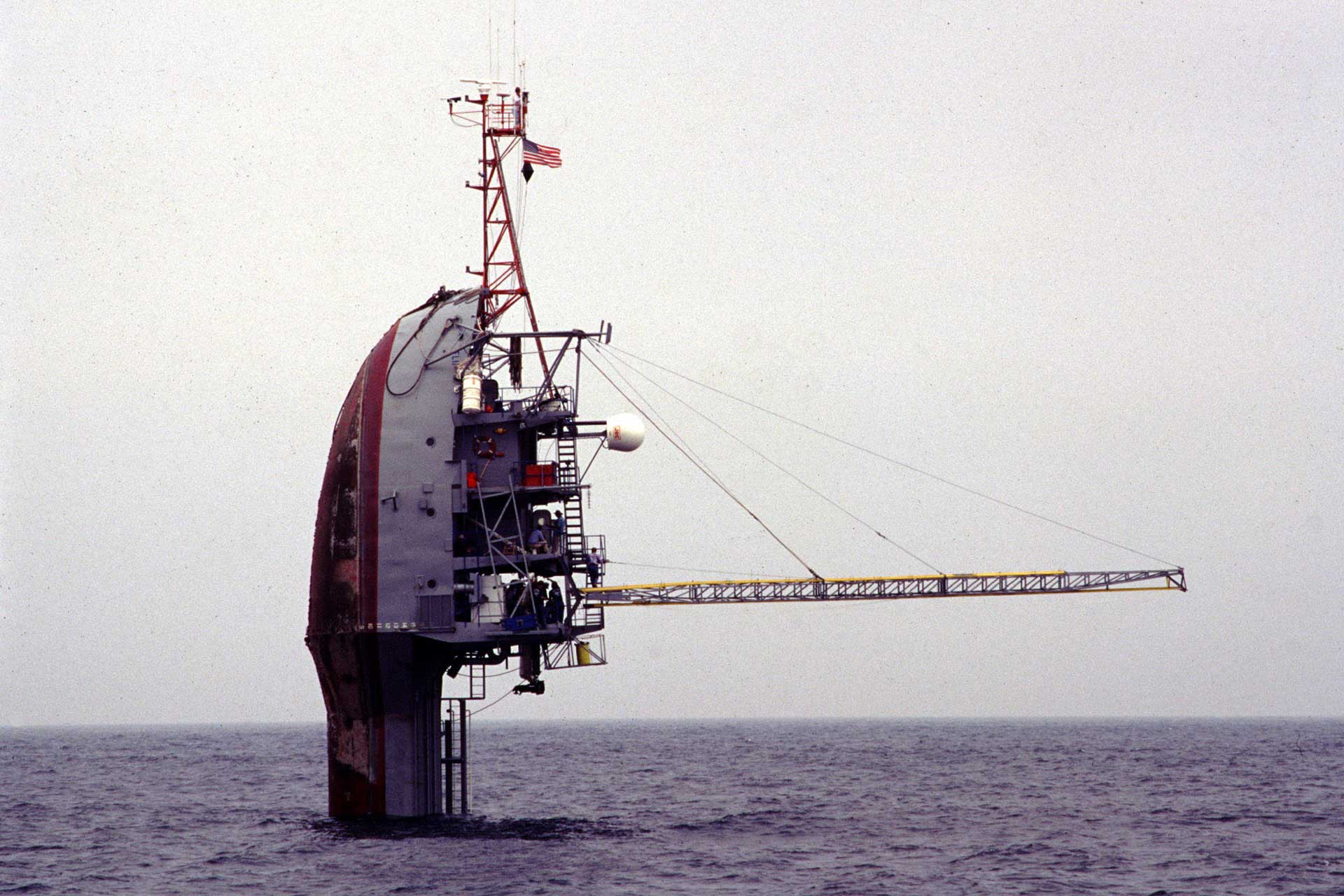

It can be said that some modes of research in science are either applied or pure. Naomi Oreskes, historian of science, argues otherwise. She articulates in her new book Science on a Mission: How Military Funding Shaped What We Do and Don’t Know about the Ocean, that many branches of science are in fact «alloys», a combination of both applied and pure. Following her book Why Trust Science? published in 2019, Oreskes alludes to the financial implications in which funding, supplied by the U.S. Navy, was ploughed into oceanography research during the Cold War. A period described as the «golden age» for oceanographers, but one with grave consequences and effects for our understanding, and lack thereof, of oceanography itself. She says, «the things we do and don’t know about the world are conditioned by what we decide to work on, and what we decide to work on is conditioned by what we can get the money to study». As much as most theories in all specialisms are tainted with bias – or as Oreskes prefers to call them, perspectives – the stories in her book suggest that an «American military-industrial complex» allowed for a constrained environment in which scientists, during this Cold War period, were often restrained through their work and manipulated by an overarching navy mission, under the guise of military supervision. Following World War II, the U.S. deep sea research grew as comprehension of the sea and oceans was considered essential to the U.S. Navy’s objectives. The research that was undertaken concentrated on three sites, which constitute the locations Oreskes probes throughout her research: Scripps, Woods Hole and Lamont – all of which were heavily reliant upon navy funding by the 1950s. Over 91 million US dollars of the funding for oceanography research during the Cold War was funded by the Office of Naval Research, alongside funding from the National Science Foundation. Indeed, both institutions allowed for an expanded and richer understanding of our world’s oceans, with research that spanned from ocean circulation to the origins of sea basins, plate tectonics, sea floor spreading and beyond – but at what cost?

Lampoon reporting: Naomi Oreskes years of studies

When Oreskes was studying as an undergraduate in the 1980s, researchers were considering if and how social constructs could mold the foundations of our scientific knowledge. Today, Oreskes poses a further question: why do we study some things and not others? She says, «it seemed mystifying to me that people were jumping over this question – if we don’t study something we can’t possibly learn about it». Science on a Mission argues that, as in most domains, money equals power. A pattern that dominates every operation, even when the individuals and institutions seem to be operating well at a first glance. Oreskes articulates how the attentions and trends of scientific research often ally themselves with whichever the rich inhabit. «There are many diseases that mostly affect people living in the poorer countries of the world that get little funding, because rich countries aren’t interested in funding diseases that mostly affect poor people. So that becomes a bias in biomedical knowledge, that there are things that affect millions of people on this planet that we don’t study well because nobody is funding it. This becomes an argument for diversity, not just amongst scientists as people, but also diversity in funding sources and diversity in thinking about the different kinds of motivations that can drive science». Oreskes denotes how we see research in all areas being framed by ideological positions. Her previous work in Merchants of Doubt looked at the way in which scientists have worked to obscure hidden truths: from the effects of tobacco smoke to issues of global warming. Correspondingly, she also notes the way in which pharmaceutical and chemical companies have commended science that advocates for hypothetically harmful products in Science on a Mission.

Harald Sverdrup – dynamic oceanography from Norway

In the first chapter, Oreskes observes the weight of political influence in science, specifically in relation to an environment in which American nationalism emerges as paramount to the investigations of science – rather than the expertise and proficiency of the individuals working. Harald Sverdrup, a leading figure in the field of dynamic oceanography from Norway, joined Scripps as Director in 1936 and was soon to be confronted with difficulties when members of his faculty became uncomfortable at the idea of Navy patronage and how that could affect the foundational purpose of their research. The right-wing laboratory scientists under Sverdrup’s wing, Denis L. Fox and Claude E. ZoBell, raised their qualms when a representative of the Navy’s Bureau of Ships came to head a university project. Oreskes writes, «like later opponents of military funding of academic research, ZoBell’s opposition was based on a commitment to academic freedom and concerns over the twin threats of secrecy and state control». Later, criticisms of restrictive academic freedom arose during the Red Scare era around the perceived threat of communism in the U.S.; at the time, these concerns were voiced by people on the left, but the 1930s era concerns were voiced by people on the political right. Oreskes says that to write this chapter «we had to file for freedom of information requests, and it took quite a long time to get the documentation». She explains that herself and a colleague had both learned about the story and had both independently filed for freedom of information requests. It made sense for them to decide to join forces and, having both been sent a set of redacted documents, they realized that upon receiving them they had each been sent documents which had been redacted differently. «When we pieced the documents together it was mostly there. I’m a big fan of government inefficiency – it makes my work possible».

State funded science

As Oreskes explores towards the end of her book, in a section titled The Context of Motivation, political beliefs have historically constructed scientific intentions. She notes how scientists in the Soviet Union believed in the origins of dialectical materialism – a philosophy developed from the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Akin to the way in which Chinese scientists have been known to adopt Mao Ze Dong’s thinking, using science to guide policy making and government principles. Oreskes says, «you’re never going to be completely free of politics and ideology in any human activity. The idea that a person could ever expunge their perspective, their values, their biases; that’s just not a realistic expectation. We are not robots, and we don’t want to be robots». The stories of individuals and pioneers in the book are largely white and male – a testament to the fact that much research across fields still exists in an echo chamber of voices that doesn’t represent our diverse societies. Oreskes concurs, «one potential critique of the science conducted during the Cold War is that it wasn’t diverse. It was mostly white men, and it was also not diverse in terms of funding – almost all the fund- ing was coming from the U.S. Navy which did lead to significant ignorance». She continues, «one of the lessons in the story of Science on a Mission is that it’s bad to put all of your eggs in one basket; if all your science is being funded by a singular funder, then you do have this risk of creating blind spots because the funder may not be interested in certain things – it doesn’t mean the funder is evil or bad, the things the funder is interested in may be totally legitimate».

The collective accomplishments of science

We learn through the events of the Palace Revolt at Woods Hole, how scientists themselves worried about undue influence by a single funder. Similar to the case of Sverdrup in the 1930s, the scientists working at Woods Hole felt an overarching sense of discomfort at the fiscal contributions from the Navy and the effect it would have on the institutional commitments to genuine scientific discovery. The director, Paul Fye – a chemist whose expertise lay primarily in warfare capabilities than in oceans, wanted to align the institution’s research priorities with the needs of the U.S. Navy. In contrast, scientists led by Henry Stommel and William von Arx, two scientists working at Woods Hole, were of the mindset that science should be driven «by individual enthusiasms among the people who were actually doing the work». Oreskes explores the motivational aspects of oceanographers at the time, arguing that the Cold War provided a «psychic motivation, by creating a sense of importance, a sense of being needed, a sense of being part of something larger than oneself». Nonetheless, she argues, «science isn’t individualistic; most of the people you see in Science on a Mission aren’t working alone, they are working in collaborations. The image we have of the isolated scientist working alone – that’s just not true. We live in countries that glorify individual accomplishments and so we recast scientific accomplishments as the work of individual genius».

Agnotology in science

While the U.S. Navy’s money expanded our epistemic understanding of many topics under

the water, Oreskes contends that ignorance was expanded too. Agnotology is the study of culturally induced ignorance. Oreskes argues that the focus on warfare deflected away from the biological fundamentals of the ocean, due to lack of funding and not fitting into the Navy’s overall mission, that are ignored throughout the book. She writes, «oceanographers in the late twentieth century constructed reliable knowledge about the ocean as a physical medium through which sound and submarines might travel, but they also constructed substantial ignorance about the ocean as an abode of life». She asserts how the Navy’s focus was primarily on physical and chemical oceanography, so as to advance their understanding of the properties of the waters in question: its temperature, density, salinity and the way it moves physically. This newfound understanding did advance our thinking in several areas of oceanography, to which Oreskes concedes – «we did learn things about the ocean, but, at the same time, think- ing of the ocean as a theatre of warfare led to a giant neglect of biological questions».

Navy investments in oceanography

Oreskes writes how, of the things ignored throughout the Cold War period, climate change failed to become a central point of research for more than just a handful of scientists working across the locations. Likewise, the balance between the physical and biological aspects of the ocean were conflated at Woods Hole where, at times, the biology of the ocean was given a back seat to the military mission. The Navy focused on what they considered necessary knowledge – investigating what was required for their mission in return for their patron- age. Oreskes explores the implications of this period in which the blind spots created by Navy investment still plague us today. «We now have a crisis in the world’s oceans: massive destruction of fisheries, of ecosystems, of mangrove swamps and of coastal regions. Damage has been done and, in many cases, we don’t even have the tools to try and fix it because we lack the basic scientific knowledge that we would need to do it right».

Why we can’t only rely on science

Though at times we see the Navy exerting control upon scientist’s explorative freedom, oceanographers had an overall positive view of the U.S. Navy as their sponsor. Oreskes writes how the Navy never impeded the scientist’s epistemological freedom and their abilities to interpret their own data. Notwithstanding some of the narrow minded Navy tactics, it cannot be argued that the Navy did not support the science – for without their support, we wouldn’t have the knowledge that we take for granted today. Oreskes writes, «a confluence of interest meant that a good deal of work that the Navy supported, was intended to answer questions about the natural world». Science on a Mission suggests that for science to be trusted in today’s world, it needs more than just scientific, technical and methodological foundations. The pandemic has exemplified how science can aid us in creating a more hopeful world, just as the same direction will be required in our attitudes towards climate change. In the context of Covid-19, Oreskes suggests that though we need science, the other components have their place too. «Science alone is not going to solve it because even now that we have these effective vaccines, we also have quite a few people who don’t want to get them and so for that – the cultural and sociological aspect of the problem – we need other resources».

Naomi Oreskes

Naomi Oreskes is an American historian of science. She became Professor of the History of Science and Affiliated Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Harvard University in 2013, after 15 years as Professor of History and Science Studies at the University of California, San Diego