From Franciacorta to Champagne, cases of experimentation through regenerative agriculture, return to traditional methods and biodynamic farming

The negative environmental impacts of the global viticulture industry

The global wine industry has had positive and negative effects on the environment. The regular use of synthetic fertilizers gradually degrades the soil and makes it dependent on its continuous use. In France, vineyards cover about three percent of agricultural land but account for as much as twenty percent of pesticide use, more than in any other agricultural sector. As a result, concerns have grown towards pesticides such as glyphosate, linked to cancer, which expose vineyard workers and people who line close to vineyards to health risks. Since the winemaking activity comprises two aspects, viticulture and winemaking, there are even more implications on the sustainability side.

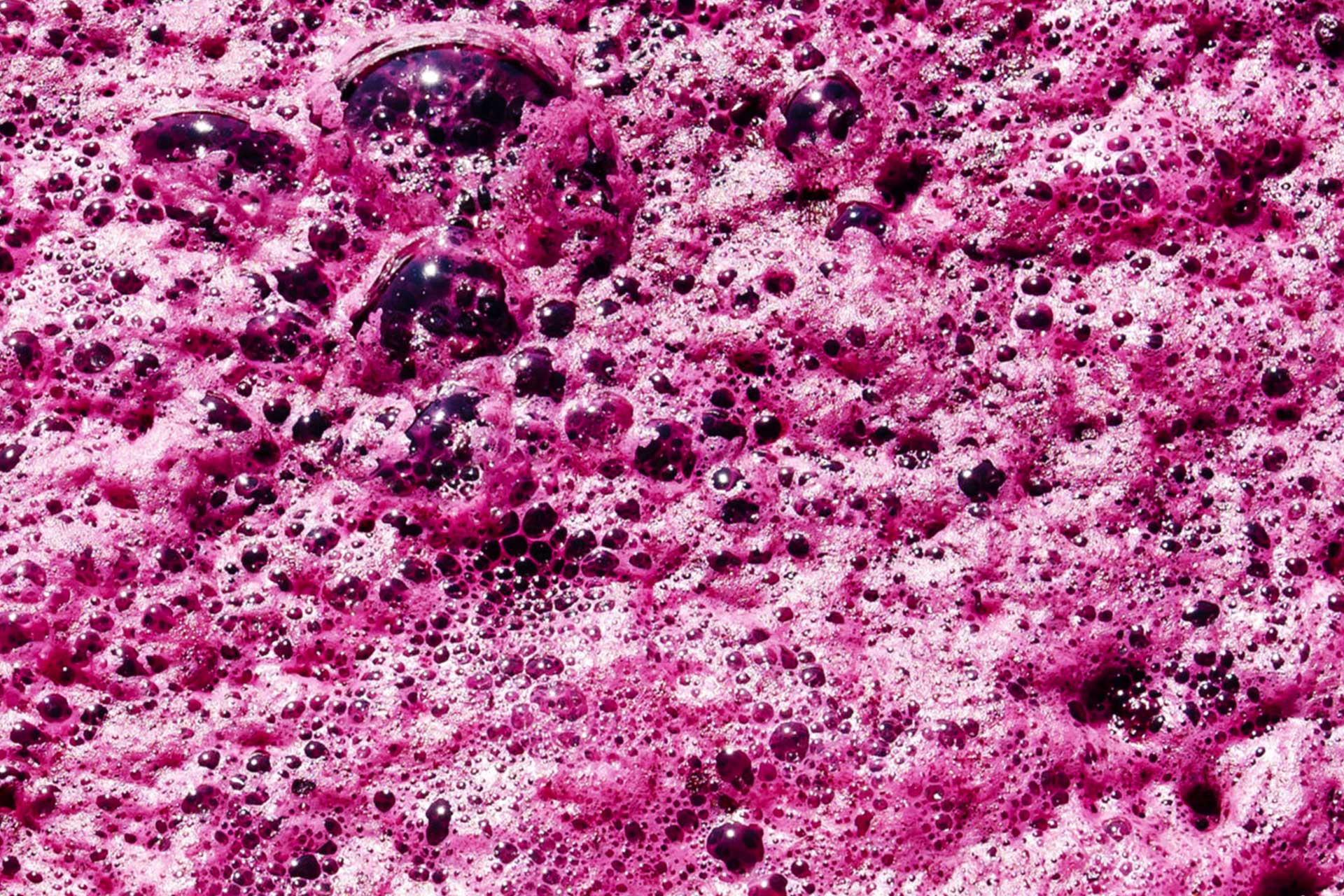

The winemaking process involves collecting grapes and turning them into wine to be sold through various methods, and these steps are not that sustainable either. Once the fruit has been picked, by hand or by machine, they ferment and turn into wine. The process of alcoholic fermentation generates CO2 as a byproduct, and the emissions released during fermentation are the most concentrated of all industrial CO2 ones. Also, in the winemaking activity, there are two types of methods: old-world and new world. While the so-called old world wines come from traditional winemaking regions such as France, Italy, and Spain, using techniques such as wooden barrels during the fermenting process, the new world wines use modern methods such as steel drums, mechanized harvesting, and screw tops and are found in regions such as Chile, Australia, and California.

Sustainable viticulture and winemaking

Wine, sparkling wine, and Champagne. The difference between still and sparkling wines is that sparkling wines have dissolved in carbon dioxide, and bubbles are achieved during a second fermentation when winemakers add to the still wine a mixture of yeast and sugars, which produces carbon dioxide, about forty times the volume of grape juice. Excessive carbon dioxide in the air can cause headaches, sweating, increased heartbeat, dizziness, and higher carbon dioxide levels, resulting in more severe and immediate effects, including asphyxia, convulsions, unconsciousness, and death, only to mention the impact on human health. When it comes to Champagne, this sparkling wine is produced exclusively from grapes grown in the Champagne region of France. It demands specific vineyard practices, such as sourcing of grapes exclusively from designated places within it, specific grape-pressing methods, which varieties can be used – Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, how much can be grown, pruning techniques, grape alcohol contents, and secondary fermentation of the wine in the bottle to cause carbonation. Champagne also requires a particular climate and soil conditions.

Climate change and global warming as a risk

The Champagne region is facing a more than one-degree-Celsius rise in average temperatures and may reach over five degrees Celsius at the end of the century. Winegrowers can adapt to a changing climate through irrigation, pruning techniques, and the use of alternative grape varieties, but many, including the Champagne ones, rely on vines and conditions. Some producers will have to move their vineyards to cooler areas or give up on the wines they have produced for generations in the longer term. Either way, the places where sparkling wine is made are set to change in the coming decades. The issue is, the global viticulture industry itself is partly responsible for climate change.

To practice viticulture, the landscape’s topography must be altered, clearing the natural vegetation from crops, wells, and terracing must be developed. Viticulture often needs to replace natural vegetation and habitat with a monoculture where only a single grape is grown. In addition, because of the regular harvest of grapes, vines keep extracting nutrients from the soil, depleting organic matter in the soil. This extensive cultivation impoverishes the soil structure and prevents the build-up of organic matter. Because of these concerns, today, there is a growing movement that addresses the role of the agricultural establishment in promoting practices that contribute to these environmental issues. Traditional winemaking methods such as Franciacorta or even Champagne aim to reduce the wine carbon footprint and restore biodiversity through sustainable viticulture.

Franciacorta method and biodiversity conservation

Franciacorta wines are produced by following the rules of the Franciacorta Wines Consortium, the most restrictive ones worldwide for the production of Metodo Classico. The production method of Franciacorta wines requires the use of white grapes of Chardonnay, Pinot Blanc, and Erbamat and red grapes of Pinot Noir and exclusively requires the manual harvesting of grapes, with natural refermentation in the bottle and the slow aging and refining in yeasts, not less than eighteen months for Basi, thirty months for Millesimati and sixty months for Riserve.

After a period of aging on lees, it’s time to let sediments flow towards the cork and then proceed to their expulsion, a process called degorgement. Bottles that are, after the remuage period, in a vertical position with the neck downwards, are placed in a solution which causes the formation of a small block of ice inside the neck of the bottle, which completely traps the yeasts deposited at the bottom because of gravity, once the neck is frozen, the crown cork is removed and the small block of ice, thanks to the internal pressure, is expelled.

Franciacorta’s efforts to protect the environment by preserving natural resources are expressed in agronomic practices and cultivation choices, starting from planting the vineyard. The Franciacorta Consortium created a tool to monitor and measure companies’ greenhouse gas emissions in order to make production more sustainable. Ita.Ca® consists of a method for measuring greenhouse gas emissions from wine growing and manufacture, obtained by adapting the IWCC (International Wine Carbon Calculator) to the Italian context through cooperation between Studio Agronomico SATA, Milan University, and institutes from other countries (Australia in particular). The goal of Ita.Ca® is to identify the emissions of greenhouse gases within the all wine production supply chain, measuring them and expressing them in equivalent CO2 emitted.

Another milestone in Franciacorta’s efforts toward sustainability is biodiversity conservation. With an area of 2615 hectares, with 120 wineries, Franciacorta has a wide range of arthropods, which are reliable indicators of soil quality because of their sensitivity to physical and chemical changes in the soil as human vineyard management techniques. Not surprisingly, the highest levels of arthropod diversity were observed in patches where organic farming had been adopted for the longest time.

The expansion of organic farming in Franciacorta results from the growing awareness on the part of individual estates that encompasses the respect for resources such as soil and water, making Franciacorta the designation area with the highest proportion – over two thirds – of organic vineyards. The méthode champenoise is the process used in the Champagne region of France to produce Champagne. This method is also the one used in various French regions to produce sparkling wines, in Spain to produce Cava, in Portugal to produce Espumante, and in Italy to produce the Franciacorta mentioned above. While the method is the same, the Champagne producers have obtained to restrict the use of that term within the EU only to wines produced in the Champagne region.

Champagne method and the rise of sustainable approaches

Maison Ruinart was founded in 1729, when Nicolas Ruinart drafted up the charter of Maison Ruinart as the first production company for Champagne. Since the very beginning, the brand has been committed to preserving the environment throughout the manufacturing process. This is stressed by the fact that ninety-eight point seven percent of all waste produced on-site in Reims is recycled, and all byproducts of the vinification process are 100% recycled. In March 2021, Ruinart began using vitiforestry – the application of agroforestry practices to viticulture, or the relationship between tree planting and grape growing that leads to changes in the microclimate of the vineyards. As Frédéric Panaïotis, Cellar Master, states, «We want to regenerate the soils and restore the original fauna and flora through these vitiforestry practices, which allow us to reestablish ecological corridors within the historic vineyard».

Considering the issues the Champagne region faces with the consequences of climate change, many houses are reconsidering their cultivation and producing practices. To become more sustainable, the Comité Champagne, which represents the interests of independent Champagne producers and Champagne Houses, works to reduce their carbon footprint, decreasing the weight of the champagne bottles, and in the waste management field, recycling winery and vineyard wastage. In 2015, the Comité Champagne also launched its Viticulture Durable en Champagne (VDC) to have the whole region certified by 2030. HVE has a weak point, which is herbicide and pesticide management, which are respectively allowed up to fifty percent of the surface and have very few if any restrictions. On the other hand, VDC promotes biodiversity, encouraging growers to plant hedges around their vineyards as well as including other sustainability rules.

Dom Pérignon embraces natural Champagne. Vincent Chaperon, Dom Perignon’s chef de cave, aims to eliminate herbicides and move toward being completely organic. While organic certification in the Champagne region remains the lowest in France, with less than three percent of the surface covered or in conversion today, compared to eighteen percent in Alsace, which is part of the same political region, many Champagne Houses are committed to improving sustainable approaches and think of sustainability as the way to preserve the soil, which is the source of Champagne final product.

Alternative solutions: biochar, regenerative agriculture, and vineyard training methods

Regenerative agriculture is a form of cultivation that attempts to reverse damages caused by human activities, such as chemical pesticides and fertilizers, by rebuilding organic soil matter and restoring degraded soil biodiversity. The result is increased carbon drawdown and improvement of the water cycle by increasing the water-holding capacity of the terrain and biodiversity above the soil, attracting benign insects to counter pests. A component that gained popularity in regenerative agriculture and in viticulture is biochar. Biochar is produced by pyrolysis of biomass in the absence of oxygen. It is used as a soil ameliorant for carbon sequestration and soil health benefits while boosting microbial populations, regulating potential pests without pesticides.

This method is used in soils with low organic matter, or terrains that have been degraded due to years of conventional farming and because of this has gained popularity in wine growing regions, such as in the Italian region of Chianti, in Tuscan, to improve the sustainability of land use for the transition towards agroecology. As explained by Francesco Primo Vaccari, an agronomic researcher at CNR IBE in Florence and vice-president of the ICHAR Association, «we approached biochar in 2007 and began to ask questions about its possible applications in agriculture. […] Over time, we also understood that biochar works especially well in drier years compared to years with a normal rainfall pattern. This is a key finding because it makes it clear that biochar serves where and when its intervention is needed, whereas if the crops are optimal, this does not bring much benefit».

The biodynamic approach

Apart from regenerative agriculture, another method to decrease dangerous and polluting chemicals is vineyard training, as explained by Jacopo Vagaggini, an enologist who experiments with vineyards with the least possible chemical intervention to preserve the environment and deliver more authentic wine. Vagaggini experimented with traditional pruning methods that have proven effective and compatible with the current environmental changes that have led to increasingly warmer temperatures. From mixed cropping to enhance biodiversity to planting vines at a distance of seventy centimeters from each other in order not to require any processing except the pruning of the shoots in winter and their binding in spring, Vagaggini proved that mechanical methods could restore stressed vineyards and enrich the soil, all without the need of fertilizers or chemicals.

According to the Biodynamic Farming and Gardening Association, biodynamic wine is made with a set of farming practices that views the farm or vineyard as one organism. The ecosystem functions then as a whole, with each portion of the farm or vineyard contributing to the next step of the process to create a self-sustaining system. Soils, natural materials, and composts are used to sustain the vineyard, while chemical fertilizers and pesticides are strictly forbidden. A range of animals from ducks to sheep live on the soil to organically fertilize it, creating a rich, fertile environment for the vines to grow in. From French to Italian vineyards, the biodynamic approach has become popular in the last few years, but the cost is high from the producers’ point of view. Biodynamic methods are time-consuming, labor-intensive, and expensive. Even a small addition of a banned substance (such as insecticides or herbicides) can make producers lose the certification and cannot be biodynamic again for three years.

Sustainable viticulture

Sustainable agriculture attempts to minimize environmental impacts and ensure economic viability and a safe, healthy workplace through the use of environmentally and economically sound production practices.