Glogau’s structure can be built with local waste: communities can use seawater, rainwater or water from polluted sources. Leftovers become a source of power for LED lights

Henry Glogau thinking towards the future

New Zealand, Denmark-Based architect Henry Glogau, designed a self-sufficient water solar distiller made up of low-cost materials. It all started in 2020, during his MA at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen. Here, he focused on architecture in extreme environments; «both extreme hot and extreme cold environments». These are conditions that are becoming increasingly common with the rise of global warming.

Temperatures are rising planet-wide, and humans need to prepare to adapt to less hospitable living conditions. Glogau’s way of thinking about architecture and design goes in this direction. «Whatever I do in terms of architecture or design are connected to these ideas. The way we design in current but also future climatic conditions». Working in an extremely hot environment today can mean preparing to use the same framework in a different environment in ten years time.

Understanding challenges and opportunities

He designed the first solar desalination skylights version as part of his MA. During the course at Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, they gave students «twelve weeks to come up with an idea that could address an issue within the context of the Atacama Desert in Chile». Glogau started by researching Chile’s climate and social background and reaching out to a local NGO called Techo Chile. They work with informal settlement communities. Informal communities in the south American country have been surging during the last decade.

The pandemic further increased this issue. This is due to both socio-economic and historical reasons: «I learned there was a huge rise in informal settlement communities, growing into Antofagasta, the area I was focusing on. This has mainly to do with social inequalities, especially after the Pinochet dictatorship». A key element of the process was «understanding the challenges faced within these communities». In the case of Chile’s informal communities, one of the main issues is that they are disconnected from formal systems. These include aspects such as electricity, sanitation and freshwater sources. On the other hand, Glogau also observed and took the opportunities offered by the territory into account. First of all, an «abundance of seawater». Climatic conditions are also very hot and dry, meaning an abundance of solar energy. After knowing challenges and opportunities and having studied climatic conditions, it was all about «how to piece the puzzle».

Henry Glogau – Solar desalination skylights

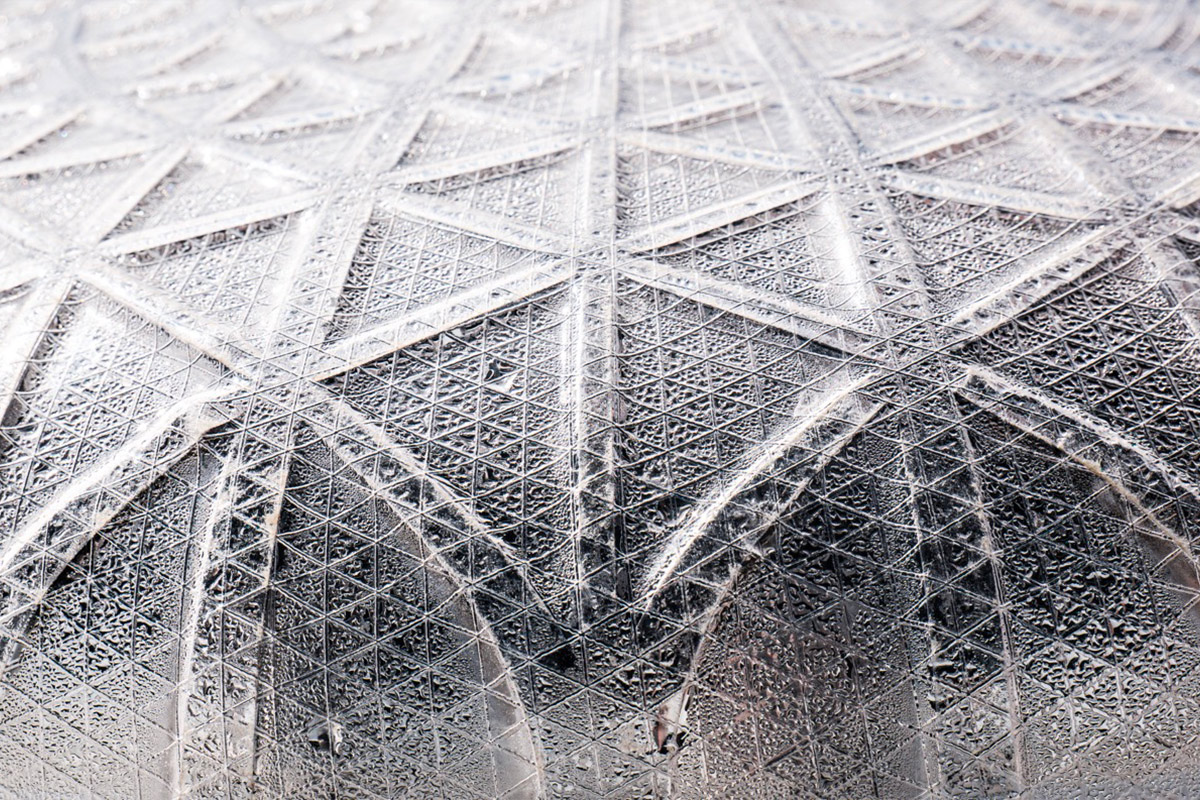

«The idea that came up was trying to create some form of autonomous resource production». This is so the communities won’t have to rely on the governmental system. They don’t always provide them with the resources they need. The idea was to enable the community to «create their own resources with what they have available». Glogau first created a hybrid design: providing light to internal spaces with a skylight. It is an autonomous source of freshwater at the same time. The desalination process is similar to the way the hydrological cycle works in nature. For instance, this is how a puddle on the ground works. Throughout the day, the sun heats up the puddle, the water evaporates into the sky, and then it inevitably goes back into rain, giving birth to a circular cycle. «What I am trying to do» Glogau explains, «is to apply that same principle but within a controlled closed loop system». The idea is that the evaporation process – powered by the natural and readily available source of the sun – will leave all the impurities behind and provide a source of drinkable water.

Using leftover salt bream: no waste cycle

Glogau then took the design further: «I knew the process created a waste of salt brine leftover from the process. Instead of discarding that salt, I thought there was an opportunity to create an energy source». He makes simple seawater batteries from copper and zinc, using the salt brine as a connecting reaction between them. Having an autonomous source of energy, they don’t need to be connected to a national grid. «This then provides communities with a little LED light source throughout the night, that can be charged during the day with solar energy».

Step forwards on the field

Glogau first took a prototype made in Denmark to Chile. Thanks to on-the-field observation and local knowledge, new ideas were born. First of all, regarding materials. «When I was there, I came up with a completely new initiative. It was the same idea but working with local communities to make it out of materials that they had readily available». He achieved this by holding a workshop with forty or fifty community members from different parts of the informal settlement. The goal was «looking at the different waste materials that they had available. Things like plastic bottles, plastic cans, supplies that they had locally».

Towards an open source, portable structure

The idea started to evolve. In 2021 Glogau won the Lexus design award, which provided funds, exposure and opportunities. The latest version looks more like a recipe book «of how you can create this design anywhere in the world; a step by step guide to hack and use the design in any way you like». After all, water «is not just an issue in developing countries. It is going to become more and more problematic in all of our lives». This is how Glogau ended up «creating something that could almost be like an emergency deployment pack for disaster relief in countries all around the world». Staring from local waste to build. The new idea is to create a «bamboo or timber structure and then deploy it depending on where you are». The source does not have to be seawater. Communities can harvest rainwater or use water from a polluted source instead. This depends on what is more readily available. It also led to the broader architectural question of «what these communities could look like if we start incorporating resource production into our everyday life». This is leading from transforming an idea of innovation into social innovation.

Henry Glogau using local knowledge and skills: involving communities

«One of the biggest achievements of the design» Glogau claims, would be if «the communities could start taking ownership of the idea». We must think differently. With the short-term competition framework, it becomes hard for architects to visit the sites they are working on. This has to change. «Spending time on the ground» must be valued. «It is key» he says,

«to establish connections with the people you are going to design for and make them part of the design process». Design can do more. With the skylights, Glogau intended to create an object that would become «an integrated part of people’s life so that people within the community could feel an attachment to the production of resources and it could be something they can control and is part of the living environment». As opposed to just making a design utility.

Low-tech nature-inspired solutions

Part of Glogau’s design is directly inspired by nature. When it comes to climate challenges in particular, «most of the answers are already out there. They have been for billions of years». We just need to observe and learn from biological processes. It is about «learning from and working with our ecosystem» rather than «trying to always be resilient and fighting against it». Technology is not always the most suitable solution for issues that are rooted in the way our ecosystem is changing. The desalination skylight, for one, is based on «simple and low-tech ideas that have been around for thousands of years». He is «not trying to reinvent the wheel here.» Rather, he is «trying to look at low tech and passive systems and reconsider or rethink how they can be applied in unique ways». When it comes to design for extreme environments, nature is «the first thing you need to look at: microorganisms, wildlife, how different plants survived these conditions».

Open source: hack and adapt

Design can also be open source: «Make solutions that people can hack and adapt». This also involves funding: «I am not up for the quick dollar: I want this to be something that people can take over and evolve themselves in the near future». Design can be more about concepts than objects. It is about providing knowledge rather than fancy items. This way, people and communities can adapt them to the materials they have available and the issues they need to overcome.

Henry Glogau

A New Zealand architect working at GXN, the green innovation unit of Copenhagen based architecture firm 3XN. Henry Glogau completed his Masters degree at the Royal Danish Academy. He specialized in Architecture and Extreme Environments, exploring present and future global challenges in expeditions to diverse locations.