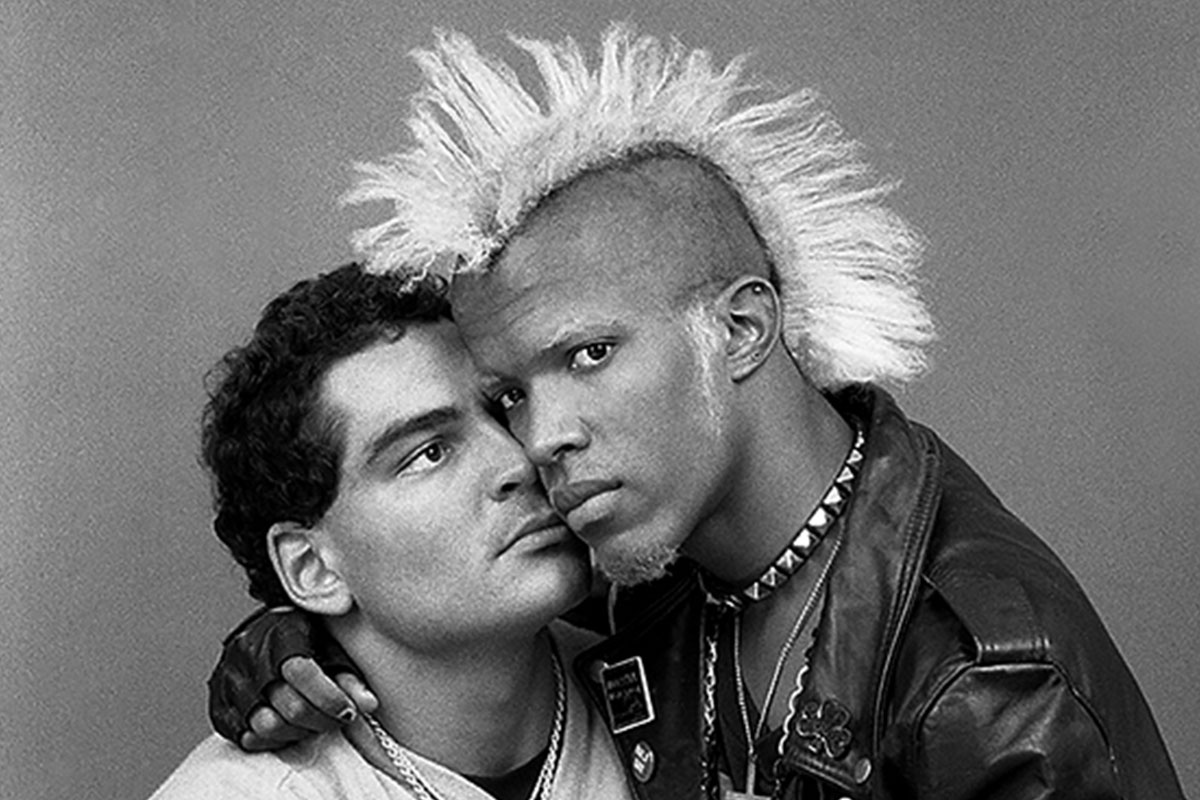

«We’ve been portrayed as degenerates or clowns, or sinners, never human. I knew I was recording something that never existed before, and that was freedom of us and acceptance of us»

As a child, he started taking pictures to keep loneliness at bay; as an adult, he ended up documenting nearly half a century of gay history. Stanley Stellar’s body of work is the largest visual archive of New York City’s queer community, but he started out with a simple intention: to point his camera at what has been ignored by the media. He depicts his (usually male) subjects mixing sex appeal with vulnerability. Interviewed for Lampoon, he looks back on the early days of Gay Liberation and reflects on the ubiquity of selfies.

KL: What lured you towards photography?

SS: My uncle gave me a camera when I was ten years old and I played with pictures all my life. Being a gay boy in Brooklyn in the 1950s and 60s I was pretty much alone, so images became my friends. For me, my greatest comfort was just sitting on the floor looking at stacks of magazines, and just loving the surprise that would come with every turn of the page. Look magazine, Life magazine, it was this era of publishing and photography. That’s what got me into it. When I went to Parsons School of Design, I thought I wanted to be a graphic designer. For a while in the 1970s I became an art director for magazines and designed coffee table picture books. I saw a lot of photographers and their portfolios. When I met with those young photographers and they would show me their prints – if they were straight men, there would always be pictures of women in bathing suits, women in lipstick and jewelry, it was endless. But if they were gay, guess what? The images were the same. It was more pictures of women. And in the mid-70s nobody was photographing men, it was almost a sin. Men were not even particularly used in commercial imagery, let alone art imagery. So by the mid-70s I started taking pictures of tattooed men on the streets of New York.

KL: Why tattooed? Was it just a good conversation opener?

SS: I had a friend who was an artist who couldn’t support herself with her paintings, and so she started supporting herself by designing custom tattoos for people. In those years tattooing was not legal in New York City; it only became legal in the late 1990s. If someone had a tattoo shop, it was clandestine, illegal and ran out of their home. And because of that, it had that caché of underground. You had to know someone, it was all very secretive and that made it all the more interesting. I started noticing that if I talk to men with tattoos on their arms, they would often take off their clothes to show me what else they had. I stopped some boy near my house one day in 1976 and asked to photograph his arm. Then, as I walked away, he lifted up his t-shirt and showed his chest, and over each nipple was a tattooed bird, a swallow. When I took a picture of it I realized I just made this candid image on the street in a genre that I’d never seen in my life. That got me into this hunt for men who had decorative, custom-made bodies, and they kept it all secret underneath their clothes. I pursued a lot of men with tattooed arms and hoped they would reveal more, and I became friends with a lot of the underground tattooists. I did that for a few years, I was fascinated by it. At some point, I thought, they don’t have to be tattooed anymore, they just have to be interesting men.

KL: Was it difficult to convince them to pose for your pictures?

SS: I’ve made it an art form, so no. I’ve never found it difficult. I don’t just walk up to strangers in the supermarket. I can read the body language and see if they will be responsive to me, this bald homosexual. Back then people were happy to express their dislike if they thought you were gay. That’s how society viewed gay people: you can live, but we don’t wanna see you.

I’m a New York City native, I’m very comfortable on the street and I know the street rules and etiquette. I know the lines you can’t cross with strangers. They were always grateful to meet me, because there were no cell phones. Everyone wanted pictures of themselves and their bodies, men or women, yet there were only polaroid cameras.

KL: Has your craft changed now that cameras and selfies are so accessible?

The whole genre of photography changed because of cellphones. Everyone can do it now. When someone like me works with them they’re a bit put off, because I don’t want them to look at themselves. I want them to pay attention to me and my camera, which means giving up control. All those selfies are not the truth at all. That’s not how everybody sees you when you’re walking down the street. I work with people on a very personal level, because most people don’t know how to direct themselves. When you work with someone else, you have to trust them. I think people often don’t know what’s wonderful about themselves, it’s their own ego that they know, not the bigger picture.

I encourage people to be so comfortable with me that they actually express their humanity. What differentiates my portraits is that I try to find that human thread between me and the model. When I see the model do something that I relate to, that I know is in me as well, then I go: click! Because I recognize it. It’s a big part of my work, especially in relation to gay people. We’ve been portrayed as degenerates or clowns, or sinners, never human. That’s always been a big theme: if someone comes into my studio, they get the opportunity to be as human with me as I am with them.

KL: I especially like the portrait you took of Marsha P. Johnson. It’s vulnerable, not the typical smiley picture.

I knew Marsha, because we were basically the same age and we came out at the same time. Most of gay life took place on a few streets in the Greenwich village. We would all go there, because it was a safe place for us to be in the daylight. I respected Marsha, because she was so outrageous looking for her time that I always felt a lot of compassion for her. I understood what she had to go through to get from her house to the West Village. She had to endure yelling, taunts… it wasn’t an easy life for her.

One day I realized I had never taken Marsha’s picture. It was a Sunday, I was walking down the street when I saw her and said, Marsha, I’m gonna take your picture. She did this toothy smile that she always did for everyone else. And that’s not my style. When people do this grin, it’s a mask. So I said: «I don’t want that, I want you to look at me like I’m looking at you» – and she did, and that’s what you see.

KL: Was it intentional or more of a surprise that your body of work turned out to be this colossal archive of queerness?

SS: Fifty-fifty. It was intentional in that I knew I was photographing a society of queer people that have never been allowed to have this much freedom before. I realized that I was in this place – when I first came out, the only way I could meet other queer people would be at night on the street or in a basement bar run by the mob. And after Stonewall we started to meet in the daylight, out in the open. And we started to see who we were – more than the images of us in tragic novels, where they always wind up hanging us or punishing us. So I knew I was recording something that never existed before, and that was freedom of us and acceptance of us.

That’s my gift with this body of work of almost 40 years. So much of queer history was destroyed. Poets, writers, painters, filmmakers… their families would destroy their work because they didn’t want anyone to know that their siblings and children were gay. They denied us so often of our own culture and accomplishments and our own humanity. That’s why I thought back then, in 1976, that the world did not need one more queer man to do more fashion photography.

KL: What is your most vivid memory of Christopher Street?

It’s only about five blocks long. It wasn’t a very popular street until gay people started walking on it. I stepped into it at the exact moment in history where it was all blossoming. Everything was softening and opening up for us little by little.

I don’t have any one moment in mind. The moment was when I realized this was my home, my base, and I felt very grounded there. People there weren’t looking like there’s something wrong with me. It changed a lot, just having that street.

In art school, a third of my class was queer. We all knew, but still – that was in the 60s – we were afraid to come out to each other. Even though we knew, we didn’t talk about it. It was too iffy, too frightening. One Saturday afternoon I walked right into a classmate on Christopher Street. We talked for about fifteen minutes and before we ended the conversation, he wanted to make sure I would never, ever mention that we met there, ‘cause he thought that would endanger him.

KL: One of your old pictures blew up on Tumblr a few years ago. It was a picture of two men in t-shirts: His and Also his. Why do you think it got so popular after so many years?

SS: Because we don’t have much visual history. If people google queer or gay, what comes up? Sex products, dildos, not a lot of richness and humanity. And the photo’s just such a simple image. It’s about «I hold you, you hold me». To me it’s honest and human.

I used to lose myself for so many hours on Tumblr. You heard what I said about images and pictures, how they became my friends. So when I discovered Tumblr, oh my God! You know what I loved about it? When people would take one of my pictures and put it on their Tumblr site in their visual context, and I would see these pictures that were very familiar to me against some printed background or something. I loved it. It’s like seeing your paintings in other people’s houses.

Stanley Stellar

New York-based photographer, born in 1945 in Brooklyn. Through his photographs, Stellar captures the beauty, fear, and love of the LGBT community post-Stonewall riots of 1969 and through the Gay Liberation movement