Thomsen gallery specializes in Japanese screens and scrolls; in early Japanese tea ceramics from the medieval through the Edo periods

Thomsen Gallery, New York

Nestled on a quiet street of an otherwise bustling area between Central Park South and the Upper East Side is a stately neoclassical building. Bergdorf Goodman, the Plaza Hotel, the Apple Store, and the once glorified, now disgraced Barney’s are all within a few blocks. In one of its duplexes it houses Thomsen Gallery. In stark contrast with its parquet floors and bay windows. Thomsen’s collection comprises Japanese artworks and objets d’art from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. I met with co-owner Erik Thomsen on a Monday morning to talk about his upbringing and his love for Japanese art. The Danish dealer was born in Chicago to Danish parents. When he was three months old, the family moved to Japan. «My father was a Lutheran missionary», says Erik Thomsen. They ended up staying ten years, between Kyoto and Shizuoka.

«Simple Japanese is not that difficult, but overall, it’s a tough language. It has so many levels of politeness», he comments on the difficulty in learning the language. Phonetic characters, in fact, are quite manageable, but kanji ideograms are far from being intuitive. «Kanji are key, though, because there are so many homophones». He remained through third grade and mastered about 300 kanji. Erik Thomsen and his brother were the only foreigners in the school. «We did many things the way the Japanese did», he states matter-of-factly.

Danish sense of irony

When their parents addressed them in Danish, the Thomsen children replied in Japanese. Moving back to Denmark was a cultural shock «I didn’t learn the alphabet», he muses. «and I wasn’t prepared for the Danish sense of irony». Allegedly, it’s an extremely dry sense of humor, which consists of saying something while meaning something else. «The Japanese have no sense of irony at all». To ease the transition — and their homesickness for Japan — their father would arrange for packs of manga comics to send to Denmark as both Thomsen children were avid readers of Japanese comics. After four years in Denmark, the family moved to America. «So I had to go to another continent». By that time, his father had become a college professor having finished his missions.

Erik Thomsen exposition to living with Japanese art

Japanese art prompted Erik Thomsen to study Japanese art history at university. Then he moved to Heidelberg for graduate school, where he continued his studies with Japanese art history, Japanese languages and added German literature to the mix. «I just always loved German literature and language, and eventually, I ended up marrying a German». He refers to his wife Cornelia, a visual artist, who is co-owner of the gallery and whose abstract paintings. Oil on canvas depicting railstraight lines in the utmost precise gradient-like scheme. To Thomsen, as relevant as his Japanese-art collection.

His father knew an antique dealer in Tokyo who specialized in Japanese artifacts and offered Thomsen an apprenticeship. At first, he framed it as a break from his studies or a way to refresh his language skills and gain fieldwork experience with Japanese art. «I wasn’t expecting I was going to become a dealer», he confesses. Going to dealers’ auctions and seeing tens of thousands of items every month and seeing the customers of the gallery — all interesting individuals — made him fall in love with the profession. He was the first non-Japanese apprentice to that dealer. Was it jarring? «I felt a little bit out of place as the only non-Japanese person there, but because I speak Japanese fluently and because they heard I grew up in Japan, they soon treated me like one of them».

Erik Thomsen opening of opening Thomsen Gallery in 2006

Once the apprenticeship ended, he spent time traveling between the US and Europe, mainly dealing through auctions. «I was traveling a lot, looking for good things». After attending his first art fair with his wife Cornelia in 1998, he had an eye-opening experience: instead of dealing with auctions, people were dealing with buyers. «I found that the most knowledgeable collectors were based in New York», Erik Thomsen says. So in 2006, with three young children in town, the Thomsens moved to New York, opening Thomsen Gallery. He understands how Japonisme seized the Western world starting in the 1850s: «there was nothing like the Japanese craftsmanship, the quality, the finesse…the world had never seen anything like it», says Erik Thomsen. By the end of the nineteenth century, everybody who had a lot of money «would travel to Asia and come back with lots of artworks».

Objects and artworks in Thomsen’s collection

From the oftentimes neglected the modern era, 1912-1940. In Western museums, you see a lot of artifacts collected from the 1850s to the 1920s. But one of the things Thomsen specializes in is the modern period. In those decades, the art market in Japan was strong. There were wealthy collectors, and collecting art was a sign of prestige; many of those who could afford it would sponsor an artist and subsidize their materials. «Artists could afford to spend a lot of time on a [single] artwork and use the finest materials», Erik Thomsen explained.

The fine arts of the period did not get exported. They were bought by Japanese collectors, while Western collectors were mainly interested in the crafts. «The Japanese wanted the fine arts: paintings, screens, scrolls, and tea-ceremony sets. Those were made by famous artists but they stayed in Japan». A measure of protectionism? No, it was too expensive to export it and there was, simply, very high demand domestically. The tea ceremony and the fine arts always had the highest standing in Japanese culture. Zaibatsu — Japanese industrial tycoons — were the main promoters of these artists. They had money and they craved status, and they (partially) achieved it by collecting it. After the war, though, they lost their prestige.

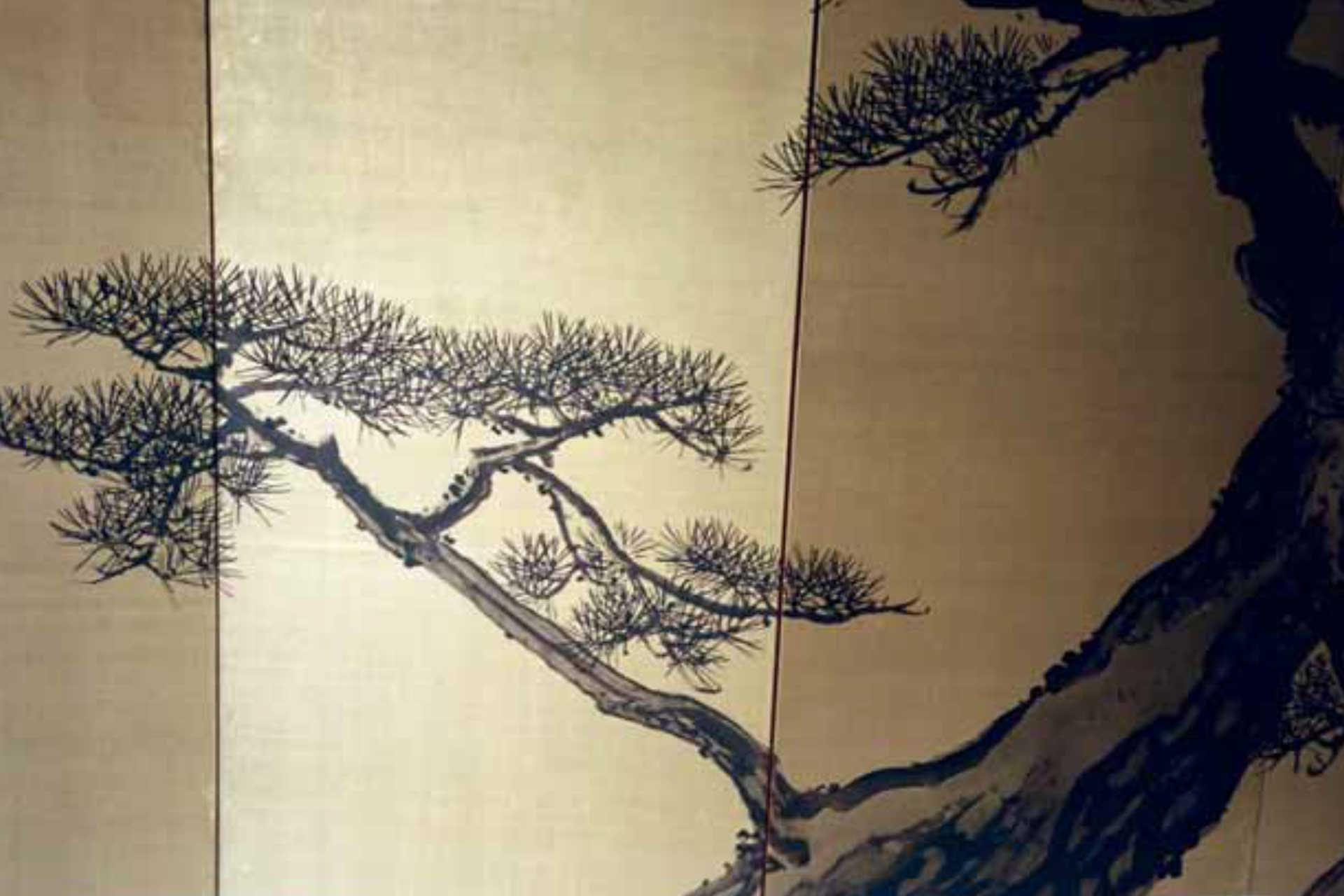

Pine Trees (1910—20s)

If we’re talking about large-scale objects, The work Pine Trees (1910—20s) by Kobayashi Gokyo presented present in the gallery consists of a pair of six panel folding screens. The artist, who lived between 1871 and 1928, is mainly known for his paintings depicting flowers and birds. Contrasting with the familiar art style of Pine Trees is the contemporary sculpture Ko (Splendid Solitude), 2018. A work by Sueharu Fukami that is a blade-like artifact made with pressure-slip-cast porcelain with celadon-colored seihakuji glaze. A technique that originated in the eleventh century in China. His collection includes tea caddies, known in Japanese as Natsume. One of them, by Teraya Kazuna from the 1990s, is made with gold lacquer on wood and decorated with a motif comprising a dragonfly and ferns, which indicates that it was used in the summertime. The turned-wood body finished in roiro (polished black lacquer) and decorated in gold hiramaki-e, kinpun, and nashiji.

Tea Caddy with Origami Cranes by Eizō Ippyōsai VII is decorated with gold-colored folded paper cranes; alluding to the art of origami custom of folding numerous paper cranes: it’s a way to bring good fortune. Tea Caddy with Cranes and Turtles by Kawabata Kinsa VI is, seemingly, more abstract. The urokozuru (‘fish-scale crane’) motif, consists of three overlapping triangles pierced with a crane’s head.Said to be the family crest of Sōen, wife of the great tea master Sen Rikyū. Its use on tea utensils — in particular, tea caddies and food boxes — dates to the nineteenth century when it was favored by Kyūkōsai, tenth master of the Omotesenke tea lineage.

Sudden Shower and Thunderstorm

On the slightly larger side, the dry lacquer box by Yoshio Okada is aptly named Sudden Shower and Thunderstorm. Its decoration, an abstract rendition of a thunderstorm, reprises some of the lacquer styles and techniques of the Momoyama (1573–1615) and Edo periods (1615–1868). The zigzag pattern, known in Japanese as inazuma (‘lighting bolt’) paired with details such as e-nashiji (gold flakes used to enhance specific areas of the design) and abise maki-e (fine maki-e lines applied over decoration executed in other techniques). By abruptly terminating the design so that it seems to disappear into the darkness of a stormy night. Reads the catalog, Okada gives the box a distinctly contemporary flavor, avoiding any sense of historicist revival or pastiche.

Erik Thomsen recalling of the kitsune

As for past glories, the kitsune, «had a spirit within it», he says. They sold it to a children’s book author. The favorite artwork he dealt was a screen titled Blue Phoenix: Seiran, by Omura Koyo. Dated 1921, it caused a stir in Japan when it was first presented to the public and a smaller version of it made it to Paris. Koyo made these screens after a trip to the Dutch East Indies, or modern day Indonesia. It’s a lush tropical jungle, with exotic birds and plants and vivid red flora, with a characteristically golden glow that the artist achieved by backing the silk with gold foil. It’s both a sensory overload and a conveyor of a luxuriant feeling of tranquility. This is the peace that invites a deep meditation on art wrote the Japanese critic Sato Rinmei in 1921. Where is it now? «We sold it to the Art Institute of Chicago», he says.

Thomsen gallery

The gallery specializes in Japanese screens and scrolls; in early Japanese tea ceramics from the medieval through the Edo periods; in masterpieces of ikebana bamboo baskets; and in gold lacquer objects. It further specializes in post-war ink art by Yuichi Inoue and Shiryu Morita and contemporary art by select artists.

The gallery is owned by Erik and Cornelia Thomsen, who live and work in New York. Erik has been a dealer in Japanese art since 1981; born to Danish parents and raised in Japan, he is fluent in Japanese and was the first foreigner to apprentice to an antiques art dealer in Japan. They have three children, Julia, Anna, and Georg.