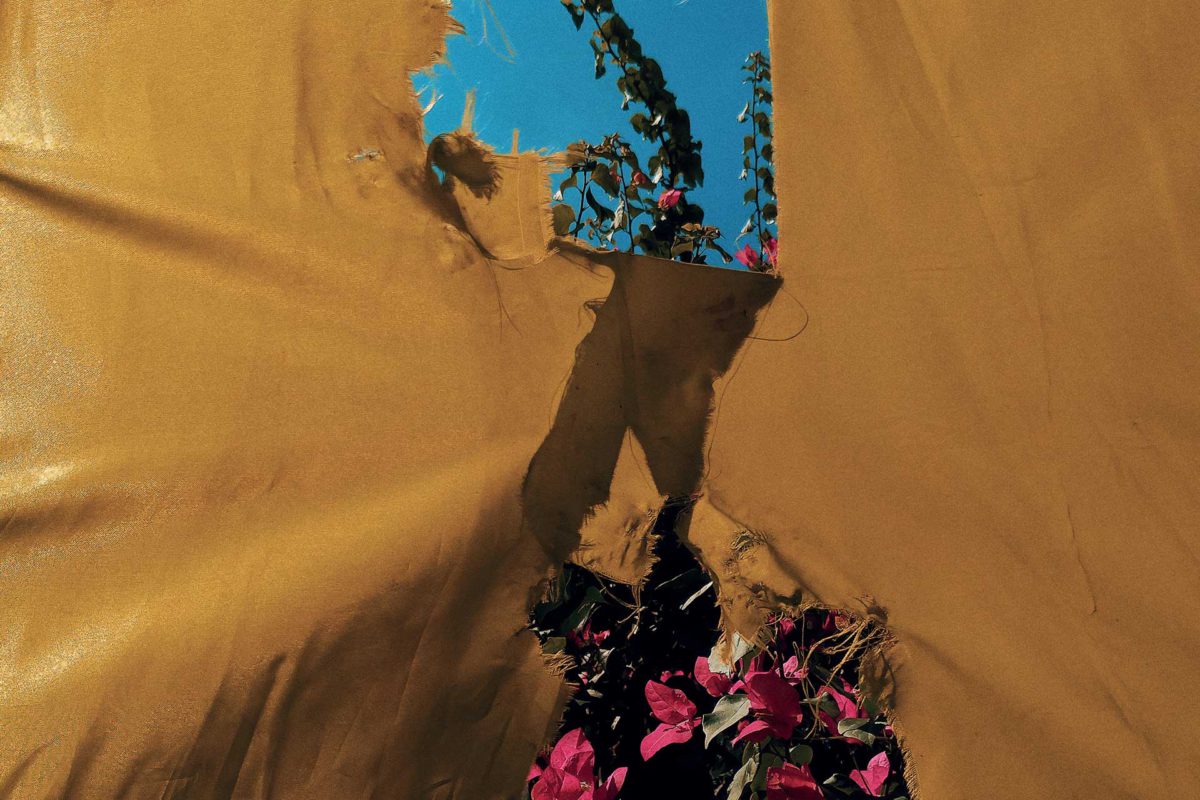

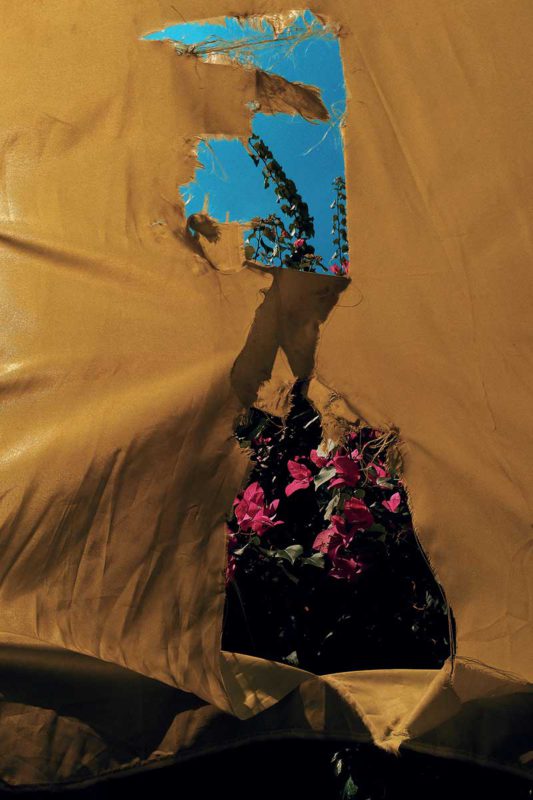

In an effort to trigger memories of Haiti, Tippenhauer began weaving raffia, raw cotton, and a variety of other natural fibers that transported her to her childhood home

Finding a shape

The shape is very human – [it] invites people to hold it», Kira Tippenhauer says of a curved pot she cradles in her hands. The piece, about four inches in height with decorative flowers and leaves painted into its glaze, is modeled after an Ancient Chinese rice cooker. It sits atop four tiny pointed feet and has a rounded belly beneath the smaller cylindrical opening. «I find a profound identity with it,» she says of this particular pot, her favorite to make and a shape she often returns to. The methodology comes from Japanese ceramics artist Akira Satake; a potter awarded the National Award in Contemporary Clay from the Philadelphia Museum.

To create the rounded bulge of a belly that gives the rice cooker pot its signature shape, Tippenhauer pushes the sides out with a ball. Tennis balls, shoestrings, knick-knacks, and other objects are used to shape the pottery. She has recently graduated from small, four inches or under pieces to larger scale vases and pots. The slab-building process, she notes, in these cases is mainly unchanged but what varies is the thickness of the clay. «I use PVC pipes, like large PVC pipes, and I use foam around it when I work larger because it’s a lot of clay, these slabs, and they get heavy, and they do need support».

Works employ a slab-building method. Slab building — as opposed to wheel throwing — is a free-form organic and multistep process to pottery. Once the clay has been prepared, it is rolled out, like cookie dough, into one large sheet of uniform thickness. Smaller pieces require thinner clay – it’s a recipe that changes depending on the size of the pottery being constructed. The sheet is then left to sit until it achieves a leather-hard state, dependent on the environment; this can take days or weeks. At the Lakay Pottery Collective — Tippenhauer’s shared pottery space in Miami — the Florida air makes for a week and a half long drying period. Then, the process begins.

It’s all about problem solving

Leather-hard state is when the clay is just as hard as a bar of chocolate that’s melting but right before it gets sticky, and it doesn’t break, it doesn’t snap». The clay is malleable and can be stretched and pulled without tearing, yet it is sturdy enough to hold memory and stay in place. A spot between soft and hard is where slab building can commence; once the clay is in a leathery state, the freehand bends it into the shape of a cylinder.

This cylinder is flipped upside down, and with four intentional pinches, the bottom and feet of the piece come into view. Tools for each possible step of the pottery process exist, but they are expensive. Tippenhauer finds the process of problem-solving to be an integral part of her practice. This process has been further illuminated through her role at Lakay Pottery Collective as an instructor.

Lakay Pottery Collective

The Lakay Pottery Collective was born as the byproduct of a desire to continue the pottery practice with financial stability. Stability of pottery practice. By «committing to a larger space and sharing it, charging a small fee for it has allowed me to afford the space to create and the time to push my work out there.» With the lease beginning in November 2018, classes and memberships to the collective started in March 2019. «I could never sustain just doing these,» she says of her pieces, «I had better months than others,” but since opening the doors to Lakay, Tippenhauer has been allotted greater peace of mind. “It’s the first time in my life where I feel like this is it — this is what I want to do for the rest of my life.»

When the process of slab-building is complete, the green-ware — in other words, uncooked pottery — is ready for the kiln. However, the firing phase of pottery is less straightforward. The three-part process begins with bisque firing. Bisque firing, or toasting, is when the pottery is cooked at about 1,100 to 1,200 degrees Fahrenheit to dry out the piece before glazing. The production of glazes takes a chemist-like mentality and understanding of rare earth metals used in formulas and combinations to create shades as shocking as neon yellows and pinks. For now, Tippenhauer has opted out of designing her glazes but says that the idea has been added to her list.

«My glazes right now are commercial, but I just met an incredible ceramics artist here in Miami; her name is Emilia Morrow, she specifies in glaze design, so right now we’re working on developing a specific palette, I want to work with some colors I haven’t see in the commercial glaze options that we have, and I realize now it’s because the metals that people use to design these colors and glazes are really expensive». She hopes to formulate two to three new glazes every year or so.

Glazes

Once the glaze is applied, it must dry for a day before the actual firing can happen. Midrange stoneware, which fires at a heat of cone 6 — circa 2,232 degrees Fahrenheit – nearly double the temperature of the bisque fire. The heat causes the clay to vitrify and bonds the glaze and clay to become one uniform piece of glass. This process also sterilizes each piece, making them both food safe and microwave safe.

It’s after the kiln that the process truly comes into its own. In her most recent collection, the classic rice cooker pots are elevated and expanded with woven textile accents incorporated into the necks of each pot – giving them a more vase-like appearance. «The clay is stone wear, and you know that the weaving is a soft material that is very fragile, yet it’s all sturdy together — the woven part softens the clay, and the clay hardens the woven part, it kind of like symbiotically communicates that it’s a solid piece,» the artist says.

A plant called pite

The idea to mix these two seemingly mutually exclusive practices came to her during an artist residency in Leavenworth, Washington. At the time, the artist had picked up weaving as a nod to her Haitian heritage. In Haiti, weavers use a plant locally known as pite, a member of the aloe family, to incorporate anything from hats to chairs to hammocks and wall hangings. The plant is left to dry, becoming fibrous and stringy – ideal for weaving. The appearance of woven pite is similar to that of raffia, which is where Tippenhauer’s weaving practice began.

To trigger memories of Haiti, Tippenhauer began weaving raffia, raw cotton, and a variety of other natural fibers that transported her to her childhood home. Still, she found herself unable to finish weaving. «I was doing both potteries, and I was weaving as well; I never finished a weaving…I always have a goal, I never finished it». However, during her residency, inspiration struck. «One day I decided to combine this tube that I made out of cotton rope, and I put it on top of a piece [and] it fit perfectly; it wasn’t planned, and it looked amazing, and I was just like, I have to put holes in my pieces so that I can attach these top parts to make vases.»

Whether it be within her identity as an immigrant or in sourcing her fabrics and fibers, the idea of duality plays a substantial role. The artist sources her natural fabrics and fibers from a farm in New Zealand, emphasizing sustainable practices and plant-based organic fibers — a far cry from the wool industry the small country is known for. The farmer raises silkworms for silk production — which arguably isn’t precisely vegan- and in their methodology, this return to the ever-present idea of dualism occurs.

By feeding the worms a differentiated diet, the silk produced differs. Light and white, soft and silky, while the other is dark and brown and coarse to the touch. The ability of the same silkworms to produce such varied fabrics mirrors human nature in and of itself. Tippenhauer’s work is a nod to the yin and yang that define humankind in the tactile contrasts of rough and soft silk or woven textiles and solid stoneware. «The truth is,» she says, «you have just as much capacity to do good as you do to do bad.»

The complexity of simplicity

The pervasive history of ceramics throughout prehistory to the current day on every corner of the globe poses it as almost an innate quality in human development rather than a unique art form. The ancient Chinese rice cooker central to Tippenhauer’s work has been discovered in other regions of the world where contact at the time of conception would have been logistically impossible, such as MesoAmerica. This tactile and practical art form, which combines a scientifically rigid methodology juxtaposed with creative liberty, is in and of itself a manifestation of dualism. Silkworms, humans, and even pots have dark and light, soft and hard, practical use, and an emotional twist. It’s the complexity of simplicity that has drawn humans to ceramics for centuries and will for centuries to come.

Kira Tippenhauer

Artist and the owner of Kiramade, a design line of modern, handmade ceramic homeware inspired by her Afro-Caribbean roots and Haitian heritage. Kira moved to Miami from Port-au-Prince, Haiti in 2004. Since earning her MFA in Visual Arts from Miami International University of Art & Design in 2011, she continues to exhibit her collage work and ceramics locally and abroad. Kira incorporates collaborative teaching in her art practice, offering ceramic workshops and classes to people of all ages through her business.