Grinstaff’s team envisions a sustainable solution which could be tailored to fit the needs of industries from everyday-use products to biomedical applications

The biodegradable alternative to traditional glue

Adhesives are used throughout industries in different sectors and found in the vast majority of products that we use every day: from post-it notes to patches in biomedical applications. These materials are composed of a basic polymer, a polyacrylate, which is made from oil feedstocks. They are created through a process which has been optimized for seventy-five years and has developed the use of efficient procedures. Since they’re plastic derived, the problem with these types of polymers is that they don’t degrade, causing a build-up in the environment. The issue raises a particular question: is it possible to create a binder that has the same properties and performance of plastic, that would cause no harm to the environment once it’s put out into nature?

Mark Grinstaff, professor of biomedical engineering, translational research, chemistry and medicine at Boston University, looked into this question to find an answer. «By looking at the chemical structure of a basic polymer, we were able to introduce a point within the polymer in which it could be cleaved, and therefore could break down and degrade. The inclusion of a carbonate linkage to make a polycarbonate version of these polyalkylene acrylates. We wanted to make an analogue of these very well-known established adhesives and make something look and behave similarly to plastic binders but actually have different functionality in terms of its biodegradation», states Grinstaff.

His research, which initially stemmed from a student’s PhD, has been going on for around two years through developing and experimenting. From the results shown in Grinstaff’s research, with the introduction of carbonate – which is in fact a CO2 linkage – the adhesive will be allowed to break down over time and completely return back to the environment. This could lead to different phenomena such as getting glycerol from corn or CO2 from the atmosphere. We tend to perceive carbon as a polluting gas – and it can be, in excessive amounts – but what this material does is to repurpose carbon dioxide that would otherwise go into the atmosphere. Carbon is a relatively cheap raw material, so it could be a potential winning situation for both the environment and the final consumer.

The process of making sealants from carbon dioxide

The making of these adhesives from an experimental standpoint involves the use of two monomers, which are the building blocks of a polymer structure. This first monomer is an epoxide and the other one is glycerol, a natural material found in our cells, food and agricultural products. «We are doing a copolymerization with CO2; by linking them together we can create the polyglycerol carbonate structure. Since we’re using CO2 from the atmosphere and repackaging it into a polymer, the polymer itself will break down and eventually we could reuse those monomers», continues Grinstaff.

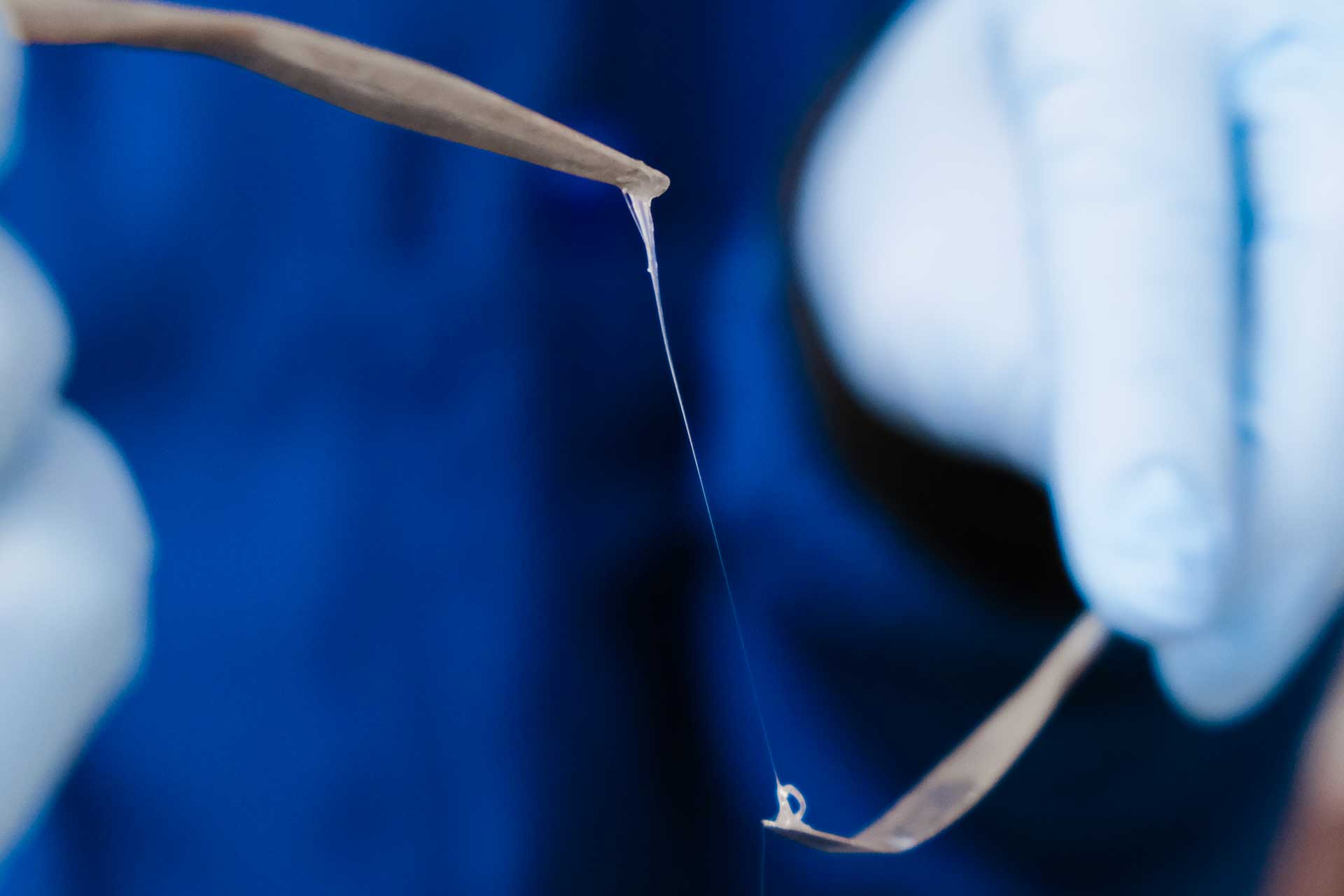

While oil products made from fossil fuels are very cheap, creating these biodegradable adhesives is more expensive because it has to be made under certain complex conditions. «We start in a gas vase: the first step consists in liquefying CO2 under high pressure; then the gas becomes a liquid and we run the reaction in it». There are no solvents or liquids involved in the making of this material. What is needed are reactors, which work centrally like a bomb. The final outcome is a material with the same appearance and viscosity as honey. Through a series of experiments, Grinstaff and his team have learned that the properties, and the performance, of the biodegradable adhesives are very similar to ones made from plastic.

Additionally, they would stick to different structures like glass, wood, plastic and ceramic, being able to bond to similar types of materials and combine dissimilar ones together. «If you push on the adhesive, it will smear and it will form a thin film and that’s what allows you to have a large surface area in contact between two structures, where you get the good adhesion from. We were able to test it on things like wood, ceramic, plastic, teflon or glass, all things that we are all very familiar with. The first test is called “peel test”, where we measure the adhesion strength; another test is the “tack test”, where you can measure its force so it gives you a quantitative way of how sticky it is», told Grinstaff.

From laboratory to commercial use

Depending on the application, the adhesive can be created with different features. When asked if the formula can be optimized according to a certain need, Grinstaff explained that it can be adjusted from a design standpoint: «If you look at the chemical structure of a bandage, you can find a polymer chain and then pinning groups that look like a comb, that all have different sizes. Depending on the length of the carbon unit, they can have different properties that would make them more or less adherent, and so on. The different number of carbons coming down from the main polymer chain also changes the adhesive strength».

In the industry, there are hundreds of types of polyacrylic adhesives and it’s unlikely that one single formula will meet every commercial demand. By changing the ratio of polymers to CO2 levels, they are making the adhesion able to respond to certain kinds of surfaces. On this matter, the direct collaboration with producers will allow them to re-engineer and make materials that are more selective to the given application. The first contacts that Grinstaff has been making are within the clothing industry for athletic wear, shoes, and personal items — commercial products that have two substrates that need to come together using a disposable compostable entity. When speaking about the ideal utilization of this adhesive, Grinstaff pointed out that it could serve as sealant for natural fibers to reinforce structures.

Future challenges and possible applications

There are multiple difficulties to creating products in a laboratory which concern the community as a whole: «There’s a lot of scientists around the world thinking about this problem and collectively I hope we can come up with a solution to advance our society and become more efficient of the resources that we do have», specified Grinstaff. The starting knowledge base in this regard is good but since it is not yet clear which commercial applications are going to best suit the use of this type of sealant, experts outside the world of academic labs need to start investing and participating in large-scale reproduction.

Additionally, the producers and buyers of the material need to be satisfied with the requirements they seek from it, otherwise it won’t reach their commercialization standards. Lastly, the final purchaser will be looking for the same performance quality of a product that fits an environmental mindset. Are people willing to spend more money for a material that uses lab technology and which is fully compostable in nature? Speaking about the production costs, professor Grinstaff reassures that although the process is definitely more expensive during the early stages of development, they will start to experience cost savings once they get to produce larger volumes.

Mark Grinstaff

Professor of translational research, biomedical engineering, chemistry, materials science, engineering and medicine at Boston University. In 2019, Grinstaff and his team of researchers created and developed an adhesive in a laboratory that is completely biodegradable whose application could be extended to commercial use.