From Ginori’s manufacturing facility, exploring the creation of an artisanal product between poetry and powder, and insects over errors

Clara Borrelli’s work for Lampoon, the Honesty issue

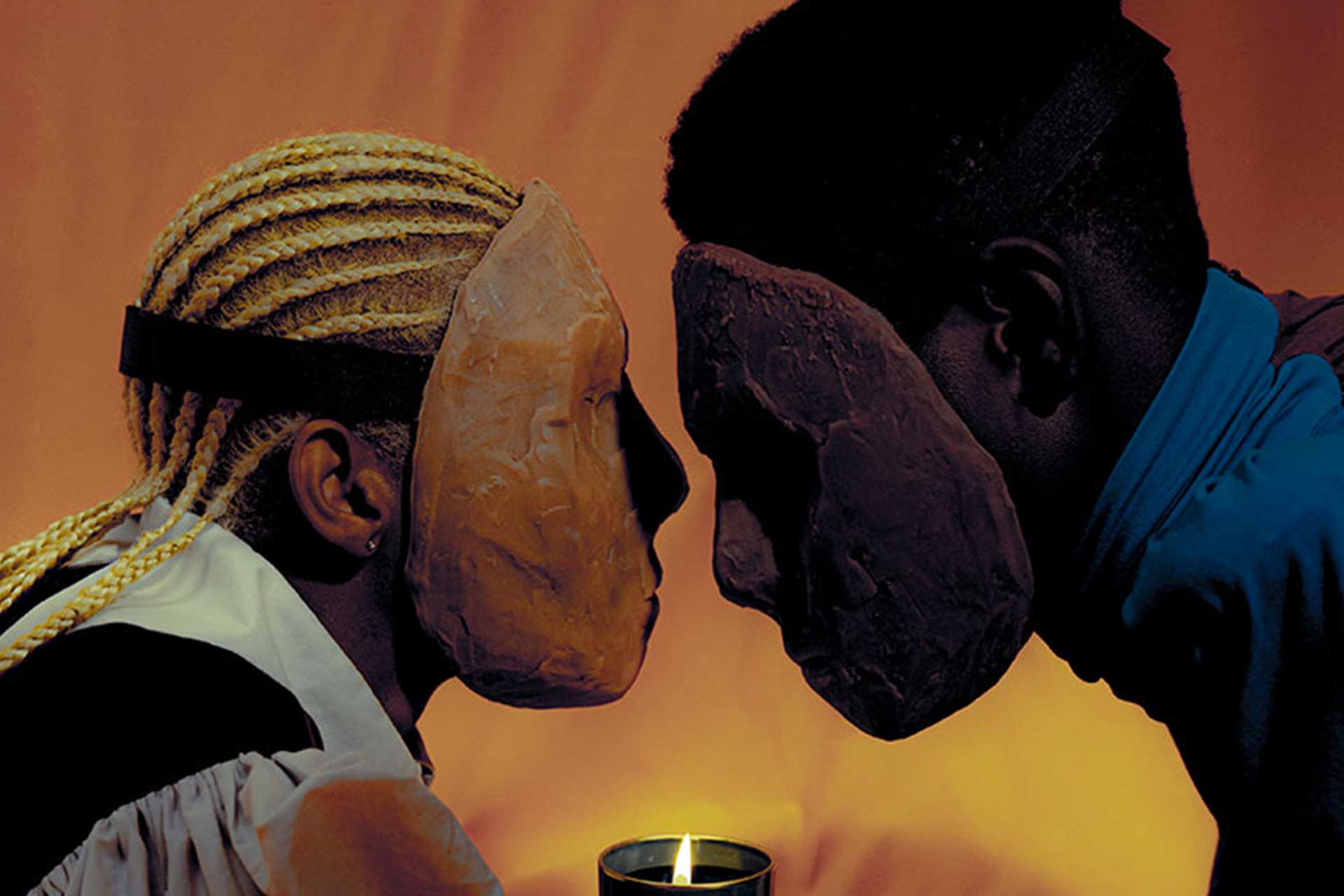

Light my Fire is the thread that binds the protagonists of the Ginori collection, characters from the past, united by an alchemy: each protagonists burns for something. The Italian photographer Clara Borrelli starts interpreting the work of Luca Nichetto for Ginori in a story called Mexican Wrestlers for Lampoon, the Honesty issue.

The beginning and rise of porcelain – Clara Borrelli

Marco Polo first encountered porcelain at the court of the Mongolian emperor, Kublai Khan. He was mesmerized by the luminescence of the material — there was no written record of it anywhere in Europe at the time — comparing it to Mother of Pearl, like the shells found in the depths of Asian seas and used as money.

He wrote in Book of the Marvels of the World: «Gold is found here; but the small money is of porcelain, which circulates in all these provinces». The Dutch East India Company introduced European courts to porcelain in the 16th century, where chinoiserie became very much in vogue as a coveted addition to any cabinets de curiosité and a prized centerpieces to display on tables or furniture. Owning a piece of porcelain was a mark of social status before it became a business, when local craftsmen found out how it was made.

Fragrance collection in porcelain jars

Along with the forks, in the Fourteenth Century Caterina de’ Medici brought to Paris what would become macarons, omelettes, crepes, soupe d’oignons and cream puffs. She brought chefs from Florence. She gave impetus to the birth of a court kitchen – and thanks to her, the tradition of French cuisine began. Caterina de’ Medici moved to Paris in 1533, after her marriage to the Duke of Orleans, Henry II, the future King of France. Her entourage included the perfumer Renato Bianco, a master of spice and plant distillation techniques. Bianco opened a perfumer’s shop in Pont Saint Michel, which became a point of reference for the Parisian nobility, who would buy perfumed essences from ‘Monsieur le Florentin’ to cover the bad smell due to lack of hygiene.

We imagine Caterina on board of a royal carriage followed by many other carriages full of luggages. Inspired by the noble lady on her way to Paris, venetian artist Luca Nichetto created in 2021 the first Home Fragrance Ginori 1735 collection encased in precious porcelain jars. Scented candles developed in sizes and colors, incense burners, room diffusers and candle extinguishers. A collection named LCDC – La Compagnia di Caterina.

Manifattura di Doccia — the first factory to make hard-paste porcelain in Italy

The Elector of Saxony, Augustus II the Strong, was responsible for the start of porcelain production in Meissen in 1710. Twenty-seven years later, in 1737, Marquis Carlo Andrea Ignazio Ginori set up a factory in Doccia outside Florence, where it soon became known as Manifattura di Doccia — the first factory to make hard-paste porcelain in Italy and the only one of its kind not owned by a royal family. Carlo Andrea Ignazio Ginori was born in Florence on January 7, 1702, the son of Lorenzo and Anna Maria di Arrigo Minerbetti. He was educated at Collegio Tolomei in Siena before starting his career as an officer to the Grand Duchy. At the age of thirty-two he became a senator and then a member of the Governing Council and the Finance Council. He supported the nomination for the transfer of Tuscan domains to the Bourbons, unsurprisingly so, given his association with the Corsini family — he was married to Elisabetta Corsini, the niece of Pope Clement XIII. But he was interested in more than just politics. He commissioned experts in hydraulics to reclaim fiefs and estates and make them productive, building villages for foreign workers. He attempted — rather unsuccessfully — to found a ‘colony’ on land near the River Cecina obtained from the Grand Duke in the Maremma area, with the intention of forming a self-sufficient agricultural system.

Manifattura di Doccia invented the ‘stencil’ technique to decorate their porcelain items

Founding Manifattura di Doccia in 1737, however, proved to be more successful; Marquis Carlo Andrea Ignazio Ginori collected more than three thousand samples of clay and minerals from across Tuscany to use for making porcelain — this became a collection he housed in his Soil Museum. He travelled to Vienna to recruit experts for Doccia, where he set up a school of draw- ing and a chemistry laboratory to train his apprentices.

Although Europe still lacked a consolidated tradition in porcelain manufacturing, Ginori started to experiment with techniques and shapes. He adapted the ancient lost wax method for casting bronze used by the Medici and successfully made even large porcelain figurines. Manifattura di Doccia invented the ‘stencil’ technique to decorate their porcelain items, compensating for its still scant painting skills. Carl Wendelin Anreiter von Zirnfeld, painter and chief decorator at the Du Paquier factory, came to Doccia from Austria in 1740 and marked the beginning of brush-painted decoration called ‘Pittoria’, which is still the hallmark of Ginori today.

When Carlo Ginori passed away in 1757, his three sons — Bartolomeo, Giuseppe and Lorenzo — took over Manifattura Doccia. However, it was his eldest son, Lorenzo, who took charge of the company and finally made it a profitable enterprise, making up for his lack of scientific knowledge by exploiting his talent in finance. He had three new kilns built and several buildings extended and updated before work began on the main building in 1776, making it more suitable for receiving visitors — the factory had become a popular destination for rich aristocrats, who were also Ginori’s top customers. His brothers, on the other hand, felt excluded and were less than enthusiastic about the plans. His youngest brother, Giuseppe, set up another factory in the San Donato villa but soon went bankrupt; the production equipment and workers were taken over by the factory owned by Ferdinando IV in Naples.

Going out of fashion

Market trends changed, just as they do today. There were more and more competitors. Rococò items went out of fashion and a more simple approach gained in popularity. Production of Doccia’s large figurines dropped as they were too expensive and outdated. Customers wanted smaller items, often featuring Arcadian subjects — marked by an attention to detail and a lack of exaggeration. The cockerel decoration was inspired by oriental designs — red and gold, and sometimes embellished with touches of pale blue — floral decorations with a single tulip or a bunch, and Western flowers or tiny roses, all introduced by Lorenzo Ginori during this period. The shapes of coffee pots were becoming flatter and more rounded; their spouts became shorter, triangular; the lids flat and their handles fancier. Cups were no longer bell-shaped as more cylindrical shapes came into fashion, with Neapolitan-style handles consisting of a series of volutes. The French style plate with six lobes.

Lorenzo passed away in 1791, and Carlo Leopoldo took over the company. He had become familiar with the French influences of the time — the Grand Duchy of Tuscany was annexed to the throne of France. The Empire style was a popular revolution. New technical elements were introduced — rectangular kilns were replaced by French oval kilns because they distributed the heat more efficiently and loads of clay were shipped from Limoges for the production of fine porcelain. Carlo Leopoldo went to Paris where he became a Chamberlain to Napoleon. He went to Sèvres to learn about production and met its technical director, who was an expert in selecting clay and the correct amounts to be used. He also travelled to England, Germany, and Austria before returning to Florence to put his new knowledge to practice.

Marianna Garzoni Venturi at the helm of Ginori

Designs changed and cityscapes appeared. The colors featured shades like chromium oxide, greenbottle, carmine, pink, flesh, or ‘air-color’ — all used in contrast with glossy enamel glazes. In 1837, a hundred years after its foundation, the third Ginori in charge of Manifatture Doccia passed away. Lorenzo II Ginori Lisci, Carlo Leopoldo’s eldest son, was still a child at the time. As a result, his mother Marianna Garzoni Venturi, took charge of the business on his behalf. The products were now dominated by a mood of historicism; past styles were reinstated, such as the de Medici vase with its rich poly- chrome decoration and abundant gilding set against a dark background — very popular at the London Exhibition of 1851. Ten years later the Kingdom of Italy was proclaimed and the capital was moved to Florence. Doccia started to receive regular orders from the House of Savoy, with the first orders including a coffee set made of the egg-shell porcelain that was so dear to Victor Emanuel II. The Khedive set was also made at this time with its almost excessively eccentric glazed line — it took two years to make it.

Lorenzo II died in 1878 and was succeeded by Carlo Benedetto. Paolo Lorenzini, the brother of Carlo and better known under the pseudonym of Collodi, had already worked alongside Lorenzo II. Electricity arrived at the factory and there were now sixteen kilns, resulting in an increase in production: there were also 1500 workers now instead of the five hundred employees of 1870. The season of eclecticism came to an end and fashion looked East, to Chinese and Japanese ceramics. Dominant themes included calligraphic floral patterns arranged loosely over surfaces. Production also start- ed to look at industrial applications — products for telegraphy and the pharmaceutical and chemical industries.

The rise of Richard Ginori

The Milan-based Ceramica Richard acquired Manifattura Ginori in 1896. Giulio Richard was born in Switzerland and came to Italy on business. His was the typical story of the enlightened entrepreneur in Northern Italy. He built houses, schools and canteens for his workers, founding a mutual assistance society and a school to teach apprentices the technical and artistic tricks of the trade. He transformed a small factory on the Naviglio Grande in Milan into large, modern industri- al premises — which now worked alongside the factory in Tuscany. Richard Ginori came as the result of a merger between the two companies. Art Nouveau was in vogue and the company embraced it. Luigi Tazzini visited the Paris Exhibition of 1900 and brought everything he saw back to Doccia: pea- cocks, flowers on long stems, flowing plants, female figures with long locks. Gio Ponti was appointed the Artistic Director in 1923, and reinstated Doccia’s classic shapes, favoring several neoclassical molds and the Empire style. Raffaello Giolli wrote in 1929: «At the first Biennial in Monza, Richard-Ginori’s stand turned this major ceramics manufacturer upside down. Small sold tags became long strips, pin to pin, and tumbled out of Ponti’s inkwells and bowls like badly shaped little snakes with large, stiff white scales. Disgust or amazement or debate filled the other stands. Everyone, from the avant-garde critic to the furniture maker from Brianza, were at one in their praise of the new ideas».

Giovanni Gariboldi, almost a pupil of Ponti, saw to the artistic direction of Richard Ginori in the 1950s. His aesthetics focused on essential lines; efficiency was a priority now, as evidenced in the vertically inter- locking Colonna set that won the Compasso d’Oro in 1954. Production facilities expanded. From the 1980s onwards — a period of post-avant-garde — Manifatture Doccia turned to the experience of Italian designers in a lengthy and prolific phase of experimentation: Franco Albini, Franca Helg, Antonio Piva, Sergio Asti, Achille Castiglioni, Ga- briele Devecchi, Candido Fior, Gianfranco Frattini, Angelo Mangiarotti, Enzo Mari, and Aldo Rossi.

The archival designs of plates from Manifattura Ginori

Plenty are the designs of adorned patterns from the archive: Gold and cobalt-blue; roses and crest-inspired design; medieval or Ottoman-inspired friezes. Amid their virtuoso-like flourishes, we occasionally see black, life-like insects crawl. They’re mainly beetles, dragonflies, flies, and bees. Just enough to startle a fellow diner, enlivening the atmosphere of a formal meal. Back in the day, inserting small insects in the intricate patterns of the finest china was meant to cover up the mistakes of craftsmen — a drop of ink, a crease, or an irregularity in texture. Rather than concealing the imperfection, a dainty insect would highlight the error by covering it up — like a mask turning heads in the ballroom. To have an insect on the platter was a matter of pride, as it underscored how unique the artifact actually was.

Alessandro Michele, who worked for Ginori before taking the helm at Gucci, knows this all too well. Stumbling upon the insect motif while browsing the archives, he decided to recreate these alleged ‘fixer’ insects in hamster size. Those tiny drawings became refined monsters, growing in size to fit in the palm of our hands — knick knacks to be scattered around the house. But the practice of glorifying and sublimating mistakes in production has vanished, pushed out in an attempt to avoid recalls and complaints in the import-export industry. What we lose is the no-nonsense practical value of an object, something that the mid-century bourgeoisie widely accepted. They were, after all, the main customers purchasing porcelain wares — an indicator of elegance no longer associated with aristocracy.

Visiting Manifattura Ginori

Powders arrive at the factory. ‘Ceramic’ is used as a generic term for porcelain, stoneware, majolica, terracotta and so forth, whose main differences lie in blends and temperatures. The three main ingredients include kaolin, feldspar and quartz. Rough proportions call for 2:1:1 but the nuts and bolts remain a secret defined by school, district, and tradition — much like grandma’s apple pie, which follows just one recipe, and yet everyone seems to have their own take. The resulting material would be dough-like in consistency, worked under pressure in order to make a series of plates, while porcelain, by default, came in liquid form, allowing for artistic elaborations. It was destined to reach each table through a system of pumps and syphons, like the watering-system of a garden, or the work of a local plumber — every work station with its own faucet and a gun-shaped extension to fill in the molds.

Near the duomo of Florence, the factory’s cast department keeps molds and reliefs neatly aligned along the shelves. It’s here that our visit to Manifattura Ginori begins, where they invent the models and shapes to be recreated in porcelain. The environment seems straight out of a Luis Bunuel film: light pours in from the loft-like windows on the first floor, while those working with molds carry on in silence. Dust is felt on the fingers, but not seen — clay has to be worked when moist. There are two ways to mold it, just as we anticipated: the first, and more advanced, is industrial, and meant for everyday dishes, which we use as a reference for our porcelain work. It’s a pressure mechanism for curved and round shapes, on a horizontal plane. The second is classic molding, the way Canova used plaster, or, more boldly, the way Michelangelo used stone, sculpting by hand. Our tale, however, is one that looks to recount the fascinating nature of this type of manufacturing without delving into an exhaustive methodology — allow me, then, to proceed with the latter: artistic production by hand. From the plaster department comes the model through which a simple negative obtains the mold: a cube containing the impression of the artifact.

When the artisan that has the ultimate say

The hollow shape arrives at the artisan’s workstation to be filled with liquid matter through hydraulic pumps and the aforementioned spray guns. Once filled, we wait for the liquid porcelain to adhere to the inner cavity made of plaster, which absorbs water, allowing the material to adhere to the most minute details of the mold. The variables for the thickness of an artifact are both the amount of liquid material poured, and the wait time before drainage. Opening the mold reveals what we call crudo — still soft, each mold can be used up to 35 times, after which, the plaster can no longer absorb water. The crudo has to be stored in a cool environment, covered in damp rags and nylon. It has ‘memory’ and can be molded. It will be joined to other components, both structural and decorative, through precise micro-sculptural finishes: flowers and petals showcase the craftsmanship of the artisans who have been passing down their secrets from generation to generation, learning new ones in the process. They work with borbottina, the most liquid form of porcelain used by artisans as glue. At each workstation, masters of the craft bring ideas from the style department to life, which are developed through books, aesthetic research, and trial and error. But it’s the artisan that has the ultimate say in a project with logistical problems, adjusting as they go. What artisans know, they learned from those before them, and each idea is the result of manual testing and new manual abilities. Alessandro Badii, who oversees the style department at Richard Ginori, is the first to recognize the value of knowledge shared among artisans.

The crudo enters its first oven, which extends nearly 80 meters long, and where temperatures reach up to 1000 degrees. Inserted by morning and extracted by night, the crudo becomes what is known as biscotto (bisque): a solid but porous material. The biscotto is then dunked in a mixture called vetrina (glaze) that will give it its translucent finish, and is prepared for the second oven, which burns at 1400 degrees. After this second process, the artifact is known as bianco, or cotto forte: the porcelain is shiny and translucent, and reflects our final product before any coloration (experts can recognize the quality and the provenance of a piece based on the shade of white and its brightness). Passing from crudo to biscotto, the product loses about 30% humidity, and by the time it reaches the bianco stage, the piece will have shrunk by 16%, forcing the artisan to make recalculations and readjustments, which can be better managed through experience. At each phase, every broken and defective component is retrieved, from crudo to biscotto, and even cotto forte, because everything comes from the same three elements: kaolin, feldspar, and quartz. It can be re-pulverized and re-amalgamated for further use, but must remain pure, or without color.

A matter of temperatures

At this point, the artifacts are colored, and head back into the oven. Cooking for color, temperatures are kept below the 1400 degrees of the bianco cotto finito, leaving its physics stable and the object solid: every time an object is cooked in the oven, it’s subject to stress, and hardened, making it more fragile.

The brightest colors are those that cook at 800 degrees: they’re called ‘third-fire’ colors, and they stay on top of the enamel. They’re strong and bright. Golden hues, for example, have to be deposited on top of the enamel, otherwise they lose their sheen. Colors that cook between 1200 and 1400 degrees are those typical of porcelain: the enamel softens again at these temperatures, and pigments slide underneath, entering the substrate of the material and of the glass patina. Colors will resist wear, losing their brightness, but they’ll be more intense and somber, in line with this art form. After all, sparkling finishes are more of a mass-market aesthetic anyway. Hues here range from cobalt blue to burgundy, green, and black — jewel tones, that refer to lapis lazuli, a pigment originating from a blue gemstone.

Ginori 1735

The name Ginori 1735 refers to the eighteenth-century origins of the company, when the Marquis Carlo Andrea Ginori launches the future Manifattura di Doccia in Doccia, in the villa of the family estate

Editorial Team

Photography Clara Borrelli, styling Sara Padalino

Photography: Clara Borrelli

Styling: Sara Padalino

Set design: Elisabetta Sapia Goya

Casting: Greta Brunelli

Hair: Alivia Lanzi

Light: Alessandro Luisi

Make up: Giorgia Venturino and Beatrice Tell

Thanks to: MTOF, Reamerei, Ardusse