Current good taste has eroded an orthodoxy that began to crumble in the Seventies: design is today emptied of its original political militancy – worse still, it can be the complement of a furnishing

The Origins of Design and the Role of Ornament in Architecture

The idea of design was born and developed in the first decades of the twentieth century as an antithesis to any meaning of décor. The goal to be achieved was a grid of abstract and purist modernity, privileging functionality, geometry and ideally mass diffusion. Ornament and Crime, written by the rationalist architect Adolf Loos in 1908, is the epitome and initial manifesto of this radical dynamism which, in contrast to the artists of the Vienna Secession, saw every ornament in architecture as a useless addition, an excess to be avoided by focusing attention on the form-function of buildings and living spaces.

The Bauhaus of Gropius and Hannes Meyer was linked to the social context, while with the direction of Mies van der Rohe, in 1930, the scenario changed and the school was given a more disciplinary character, focused on the theme of architecture. Mies himself, a prophet of ‘less is more’ who came from a youthful apprenticeship with Max Fischer, a specialist in interior stucco, was not immune to decorative seductions, especially in his use of colored marble alongside steel-framed windows and a powerful impetus from structuralism.

The Evolution of Design from Modernism to Meta-modernism

«Is form really a purpose? Or is it the result of the process of giving the form? Is it the essential process?», wondered Mies van per Rohe when he was director of the Weissenhof. Coming to un- derstand form as a purpose always leads to formalism. Away with everything, frames and ceiling coffers, sculptural moldings and reliefs, furniture sets, upholstered sofas and elaborate mirrors. Lambris, gilding and pilasters, as well as corridors all abolished, the centerpiece of a bourgeois vision of domestic life.

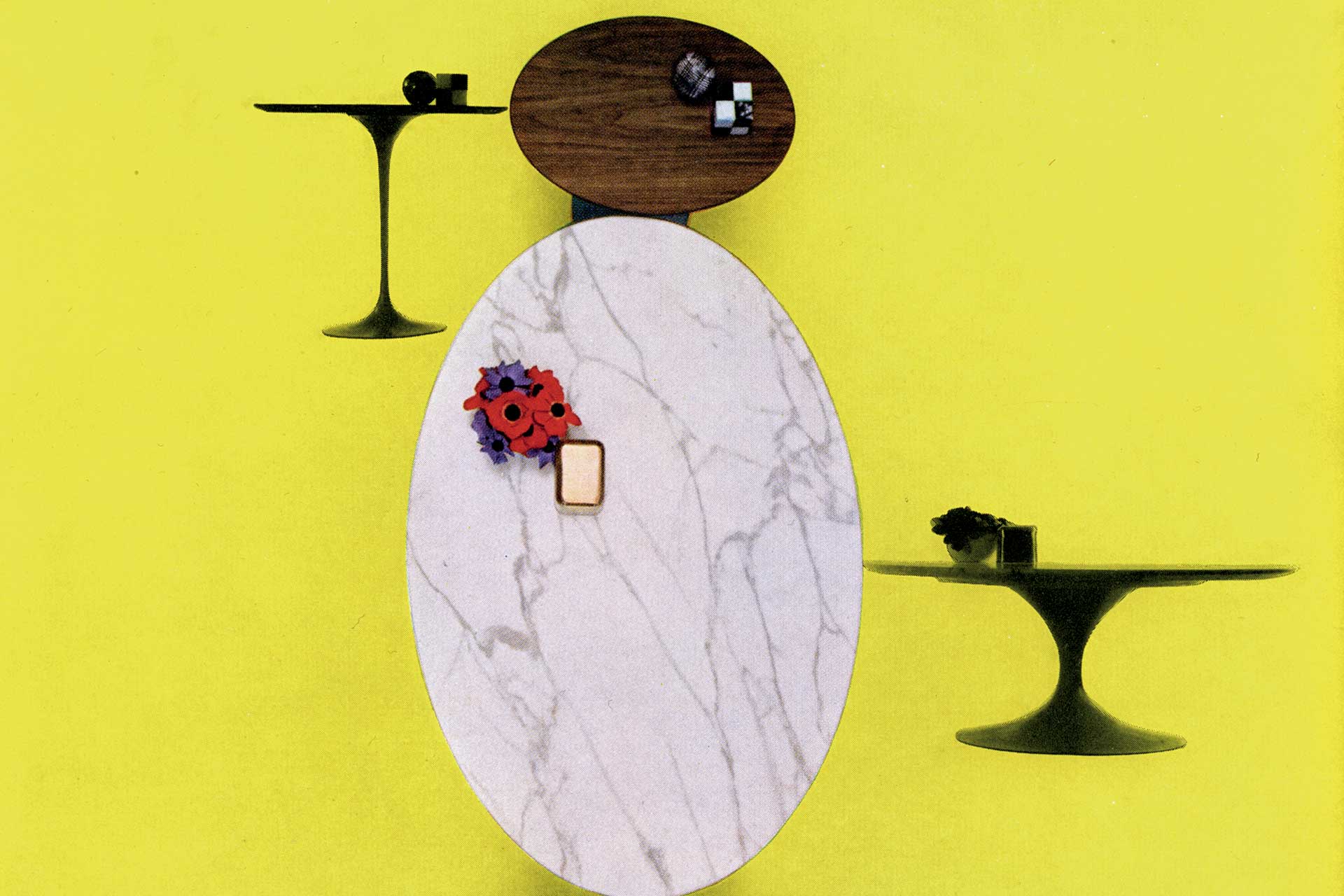

Today, the furniture design and objects of use of the Twentieth century – those pieces that have gone down in history, such as the Bauhaus replicas, the creations of Caccia Dominioni, Magistretti, Angelo Mangiarotti and Carlo Scarpa, or the iconic Tulip table imagined by Eero Saarinen in 1957 – represent the opposite of the revolutionary and egalitarian scope that characterized their primary imprinting. The certainties and messages of Modernism cracked in the nostalgic compositions of the post-modern Eighties, only to collapse completely in the stylistic melting pot of contaminations and boutades typical of meta-modernism.

Design, whether it be of yesteryear or of current production, is today emptied of its original provocation and conceptual and political militancy. Worse still, as a status-symbol, it can be the complement of chic furnishing. Consider the case of Jean Prouvé, communist and friend of Abbé Pierre, whose ‘nomadic architecture’ likened a chair to a house and included knowledge of the materials at hand, as well as collaboration between craftsmen and artists focused on technical development.

The Evolution of Design: From Militancy to Status-Symbol

For Prouvé, there was the principle of ‘not putting off decisions so as not to lose momentum or indulge in unrealistic predictions’. Who knows what he would have said when he saw his spartan inventions used in the warping of a boho living room, mixed with Louis XV consoles, or with paintings by Fontana and Castellani, or with Kapoor’s mirror that can never be missing in any home of a certain level. The armchair inspired by the angles of a drafting compass by Pierre Jeanneret, cousin of Le Corbusier and companion of Charlotte Perriand, born as a low-cost piece of furniture in 1951 during the genesis of the Indian city of Chandigar, rages like a catchphrase in any editorial or sector advertisement as a reference of taste.

Not to mention the collections based on numbered specimens of objects and furnishings, signed by the gurus of a design that is increasingly intertwined with art and with the recovery of ancestral techniques brought up to date. The Fratelli Campana, Michael Anastassiades, Formafantasma, the serial recycler Martino Gamper and a veteran like Enzo Mari. Current good taste has eroded an orthodoxy that began to crumble in the Seventies, through the sophisticated and pop solutions of Cini Boeri and Carla Venosta, while David Hicks worked with pickled woods, William Kent fireplaces, optical carpets and fluorescent plastics.

The Intersection of Design and Decor: Contemporary Trends and Historical Figures

To which sphere these métissages should be ascribed, Gio Ponti, like Franco Albini, often oscillates between the two sides; as does the neo-Hellenic luxury of Jean-Michel Franck, prince of decorators and parchemin; the stylizations of the classics by André Arbus or the mastery of Marc du Plantier, between gilded bronze, porphyry and perspex. What about the recent mass-cult acquisition of Lina Bo Bardi, Italian designer and Brazilian by adoption, forerunner of today’s debated themes – sustainability, social inclusion, sharing culture and differences or attention to minorities. Hakim Sarkis, curator of the XVII Biennale of Architecture in Venice, awarded her the special Golden Lion in memory.

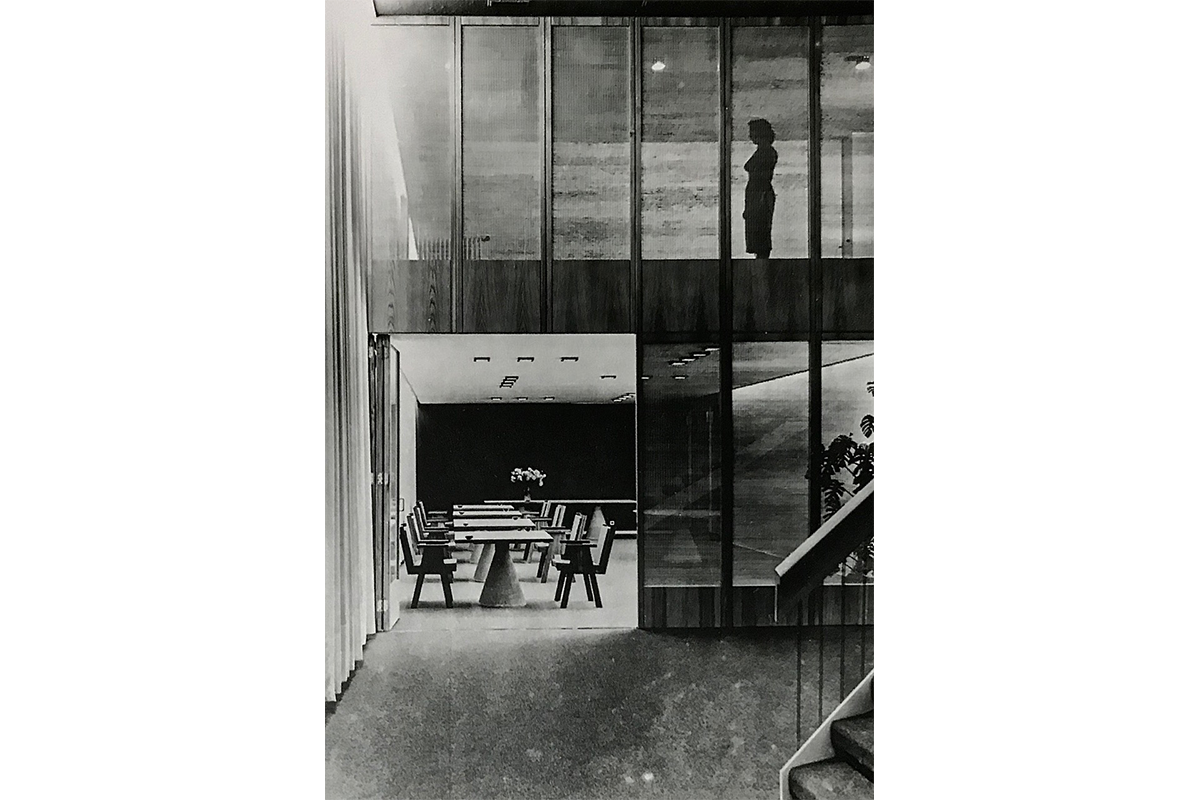

In her Casa de Vidro in São Paulo, Brazil, built in 1950-51, set in an opulent natural context and open to all that is ethical and poetic, even to the wildest storms and brought into contact with its dangers, one breathes a bourgeois perfume, a salonnier drift due perhaps to the objects of art inserted by her antiquarian husband. Whether or not they are Sanculottes, decorators or designers, they are almost always personalities who came out of the ranks of the European or American intellectual bourgeoisie, that disappearing thinking class we miss. Design vs. Décor: do we still believe in it? «Interior design is the art and science of understanding people’s behavior to create functional spaces within a building, while interior decorating is the furnishing or adorning of a space with decorative elements to achieve a certain aesthetic. In short, interior designers may decorate, but decorators do not design».

The Ambiguity of Semantics: Blurring the Boundary Between Design and Decor

Are we sure that this assumption – the source is RMCAD’s Interior Design Program – is entirely to be shared, in an era in which partitions and classifications are increasingly fluid? Categories and definitions today overlap and precipitate into disharmony, into a libertarian anarchy that swallows and reinvents every- thing without fear, philological hesitation or taboos. Considering that décor includes such leading figures as Lady Mendl, Emilio Terry’s Louis XVII, the baroque verve of Dorothy Draper and Madeleine Castaing, where can we place imaginative überdecorators, praised as unconventional innovators, such as Mongiardino and Piero Fornasetti or, to return to the present, the transepocal independence of Jacques Grange?

Should the work of Francois Catroux, the Flemish Volledig of Axel Vervoordt, the stylizations of the Sills Huniford duo in the 1990s, and the minimalism of Vincent van Duysen be considered décor or design? Ambiguous semantics also apply to the Miller House in Columbus, Indiana, designed by Eero Saarinen for his friends Xenia and Joseph Ir- win Miller, the ‘Medici of the Midwest’, in 1957, with input from Kevin Roche. The boundary between design and decoration here inter- faces in a flexible geometry, often compared to Palladio’s Rotunda for its modulation and sacredness. The expressionist classicism that Cy Twombly deploys in his own residences, starting from the canonical one in via di Monserrato in Rome, immortalized by Ugo Mulas’ images in 1969-70, is now on the terrain of art.

The Subtle and Complex Relationship Between Design and Décor

The same applies to the Montecalvello castle, Bal- thus’ Latium home, ideal persecution of his suspended and ambiguous pictorial spaces. Neutra and Schindler in the USA were imitated by endless followers, who fragmented and weakened the lively Bauhaus philosophy they brought with them from Mitteleuropa. Luigi Nervi, in the Italian Embassy in Brasilia – 1971-77 – conceives a contemporary version of the grandeur of a classic diplomatic palace, grafting it onto a forest of concrete tetra- pods. He revisits brutalism with a lavish sinuosity. Rem Koolhas indulges in a somewhat costumed exercise in Porto’s Casa da Musica, completed in 2005, in a constant relationship between interior and exterior that contrasts with the decorative scheme of traditional azulejos and eighteenth-century furniture set against walls of corrugated glass.

Marta Sala, nephew of Caccia Dominioni who founded Azucena in the Foutries along with Ignazio Gardella, has entrusted Marta Sala Editions (MSÉ) to the architects Lazzarini & Pickering, that have given a fresh twist to the key contents of a Milanese bourgeois sophistication. The game of contrasts, diversities and similarities that is established between design and décor is very subtle and complex in its affiliations and characteristics. It also depends on the credibility or otherwise of the client, on the social representation that is aimed at a specific living environment, within a domestic or public enclosure.

Paola Antonelli, Director of Research and Development at MoMa, with Applied Design, a reinstallation of the collections that takes place once a year, underlines the many forms of design, which is not only about machines and fashion, but also about interface design, interaction and visualization. According to Antonelli, a good designer is one who is not afraid to experiment with technology and has a good technological approach and a clear vision. There are those who deal with the future and those who experiment. «The designer who refuses to confront technology – concludes Antonelli – really has a lot to learn».

Marta Sala

Marta Sala is a Milanese design editor. Following in the footsteps of her uncle Luigi Caccia Dominioni and her mother Maria Teresa Tosi, who founded Azucena in 1947, she proposes her own collections that blend refined design with the Italian artisanal knowhow.