It takes an engineer to make things in big quantities and a craftsman to produce a wooden spoon. The British designer discusses the challenges on crafting newness

A hundred history of craftsmanship

Built in 1851 on the King’s Cross section of the Regent’s Canal, Eastern Coal Drops were imagined as an administrative and storage facility for the incoming of coal and fish supplies into London. In the 160 years since, the use of the space evolved from being a depot of a Yorkshire glass bottle company, Bag ley, Wild and Company, into one of many disused warehouses in the UK capital. In the Eighties, as rave culture emerged onto the scene enforced by techno music, the Victorian setting became a backdrop for all weekend parties and illicit drug use. Then came 1993, when the six arches within the Eastern Coal Drops got taken over by Billy and Keith Reilly (the latter being also the founder of one of London’s oldest running night clubs Fabric). The space was named The Cross and refashioned into one of the city’s most exciting nightclub interiors, which ran as such for fourteen years before it closed due to the condition of the structures becoming unsafe.

A revolutionary store opened during Victorian age

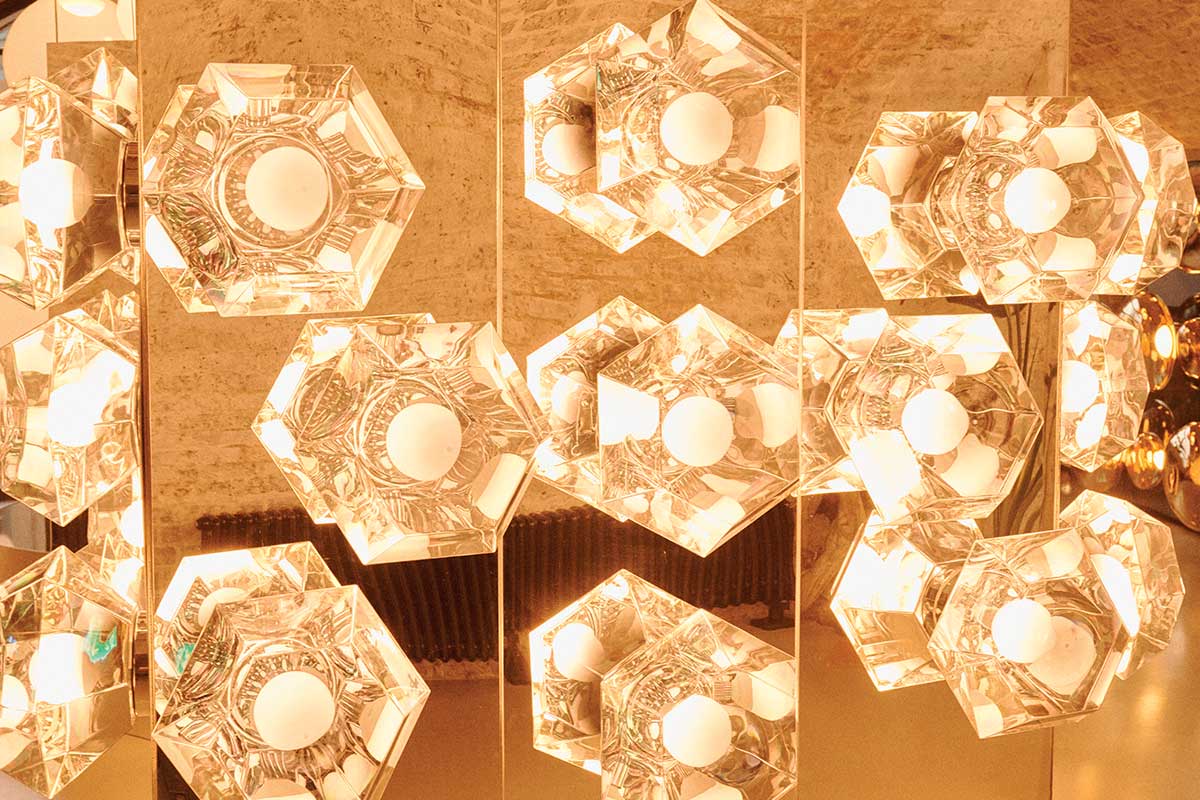

Under the joint name of Coal Drops Yard, the complex of Victorian warehouses was reimagined by architect Thomas Heatherwick and opened in 2018 as a shopping institution enriched with Michelin-starred cuisines, altogether nurturing a luxury lifestyle for the whole family. Instead of steamy floors and empty plastic ziplock bags, the six arches previously known as The Cross now hold a Fan Chair in black oak, mirror glass amoeba-shaped Melt ceiling light fixtures, and plenty more design gems courtesy of Tom Dixon. The self-taught poster man of British design has taken over the space as his flagship store, with his three-story HQ towering above. There’s also the Coal Office Restaurant, which Dixon opened in collaboration with Israeli chef Assaf Granit and is annexed to the head office.

Dixon never studied design. He first got introduced to the idea of craft and creation while attending Holland Park School. «It wasn’t great getting on there but there was proper metalwork, woodwork departments and a proper ceramics department which is quite rare in secondary school». Age fifteen, Dixon wasn’t interested in the academic aspects of his education but spent most of his time avoiding trouble in the pottery department. «It was the shape-making from a muddy lump of wet material into something hard, but also the transformation from soft to hard, and from useless to useful. That’s the conscious attraction of being able to create something».

Dixon began working on furniture as a hobby, while also playing the bass as part of an eight-piece funk fusion band Funkapolitan and running several nightclubs around the capital. During the Eighties, his focus in design was mostly on creating one-off pieces from salvage materials found in the piles of industrial waste at what’s now known as the West London upmarket complex Chelsea Harbour. Cast iron radiators, sewage components and panels of steel mesh were transformed into sculptural chairs with limited comfort and use. These early sustainable tendencies came from necessity, but were also a result of Dixon’s creative manifesto. «I feel more comfortable fighting against restrictions than just having a clean page. I would have been happy to be a sculptor or an artist, but I feel there need to be constraints so I can break free and think in a different way». As a result of the mass property development of the Eighties, Dixon’s scrapyard resources dried out which meant he had to look elsewhere for components of his chairs. Specialist mechanic stores such as bicycle and plumber merchants presented the next step in growing his business and the beginning of creating more conventionally produced furniture. One of Dixon’s first commercial successes, back in the late eighties, came courtesy of a partnership with Italian innovators in design, Capellini, in the form of the SChair, a curved shape inspired by the shape of a chicken.

A philosophical approach to his work, crediting his cultural heritage

There hasn’t been a British design movement since Arts & Crafts. While other sectors of British creativity such as fashion or architecture have birthed minds considered around the globe, it is furniture and interior design that seem to be lacking its forward-thinking names, with the exception of few. «A problem for the UK in design isn’t that it doesn’t exist, it’s just that it’s an export service», says Dixon, explaining how most British designers’ clients tend to be manufacturing companies from abroad. «There aren’t so many British brands today because there aren’t enough British manufacturing brands here that are able to support the huge design community that exists here».

Despite starting his career by working with and being influenced by Italian designers highly interested in the meaning of the objects they create and the revolutionary aspects of design like Castiglioni, Ettore Sottsass, and Enzo Mari, Dixon rejects such philosophical approach to his work, crediting his cultural heritage. «It would be a hard push to be British and put too much meaning in the object», he adds with a smile. Even at those early stages, Dixon had a bigger idea in mind as he opened his first retail outlet. Named Space, it was a store and a workshop for emerging designers to further their profession.

«I don’t think it was intentional. It just so happened that I needed more people to collaborate with. People always came and worked for me and I let them use the space in the evenings to make their own things. When I was doing the shop, I thought it was more interesting to have a multiplicity of ideas rather than just have a single designer’s work. It was just about enriching what I was doing». Dixon is aware the process is a two-way street. «I benefit as much from being a platform for other people as they do». His fascination with plurality continues to this day via Design Research Studio, a hub for development of creativity in design. In 1979, it was German futurist architect Wolf Hilberitz who patented the Biorock accretion process which uses a method quite reflecting the growth of living corals.

One of Dixon’s more futuristic projects is Batch Zero, an underwater production plant set at a secret location in Bahamas based on the Biorock process of using low-voltage current to grow mineral accretion into furniture. «These experiments are trying to work out whether there’s a community aspect or a means to generate work for people in distant communities, which is the underwater one, which morphs into an idea about carbon capture and an idea about selling futures in furniture rather than selling furniture readymade. There are lots of layers of conceptual thinking but also practical obstacles that you’re trying to overcome, which is what I like about design».

From commerce and engineering to sculpture and communication

As a brand, Tom Dixon stands for more than just the high-end products sold as part of the label. «There are all kinds of ways of making things cheap or making things expensive, and I’m interested in all of them. I started off making single pieces of things made with my own hands, I worked with big organisations. What’s nicest is the nature of the challenge which changes according to what you’re attempting. Its founder collaborated with IKEA on multiple projects and also spent a decade as the creative director of mass household furnishing store Habitat. What was so good about that job — I could do a plant one day, or I could do arts. It increased my interest in being a generalist rather than a specialist».

Dixon explains the approach that remained with him to this day. His own company has been set up so he is able to dip into most of its branches, from commerce and engineering to sculpture and communication. «I became a designer because people were interested in buying the things that I was making. It was never a separate activity to sell the stuff; it was never a separate activity to make the stuff. What is distinct and what doesn’t really get taught at the design schools is how you sell a thing or how you get it at a price that people will pay for, and that’s something I taught myself as well».While being pragmatic seems to be the ultimatum of Dixon’s design process, there also seems to be leeway in the way he approaches the work. When asked about starting from the point of a design thinking methodology, Dixon originally dismisses the idea, before taking a few seconds and softening up. «Each job has a different departure point and a different endpoint. I try not to have a specific method and try to arrive with an open mind and without preconceptions. There will be a time when, absolutely, the opposite is true and you start off with a functional consideration because that’s the challenge. But that’s the nice thing about being a designer, your landscape changes every time you have a new job».

A need for speed

With a radical approach also comes Dixon’s need for speed. «You can’t stay static in the modern world, you have to keep on refreshing yourself». At the time of writing, the London flagship store is in the middle of changing, as the plans include erecting a large 3D printer and a music studio space in partnership with Swedish experimental electronics company Teenage Engineering. «As times change, so does the idea of craft. That craft is just a hand skill is no longer true, you see kids that work for me that are craftsmen on computers. It’s something that requires a vast amount of dedication and practice to be good at. I don’t suppose there’s as big a distinction between an engineer that makes it possible to make things in big multiples and a craftsman making a wooden spoon», adds Dixon, before wrapping up our interview as his jamming band awaits in the foyer of his headquarters where a music system is set up along with designs that the Tom Dixon studio is yet to release.

Tom Dixon

Established in 2002, Tom Dixon is a British luxury design brand which is represented in 90 countries and employing more than one hundred people world-wide. Specialising in furniture, lighting and accessories, Tom Dixon has hubs in London, Milan, Hong Kong, London, Los Angeles, New York, Tokyo and Hangzhou. With an aesthetic that is intrinsically inspired by the brand’s British roots, the products are internationally recognized and appreciated for their pioneering use of materials and techniques. Founder and eponymous Creative Director Tom Dixon is a restless innovator who rose to prominence in the mid-1980s as a maverick, untrained designer with a line in welded salvage furniture. While working with the Italian giant Cappellini he designed the widely acclaimed ‘S’ Chair.