Do contemporary houses encourage wasteful living? In conversation with London-based architect and artist, Nicolas Henninger

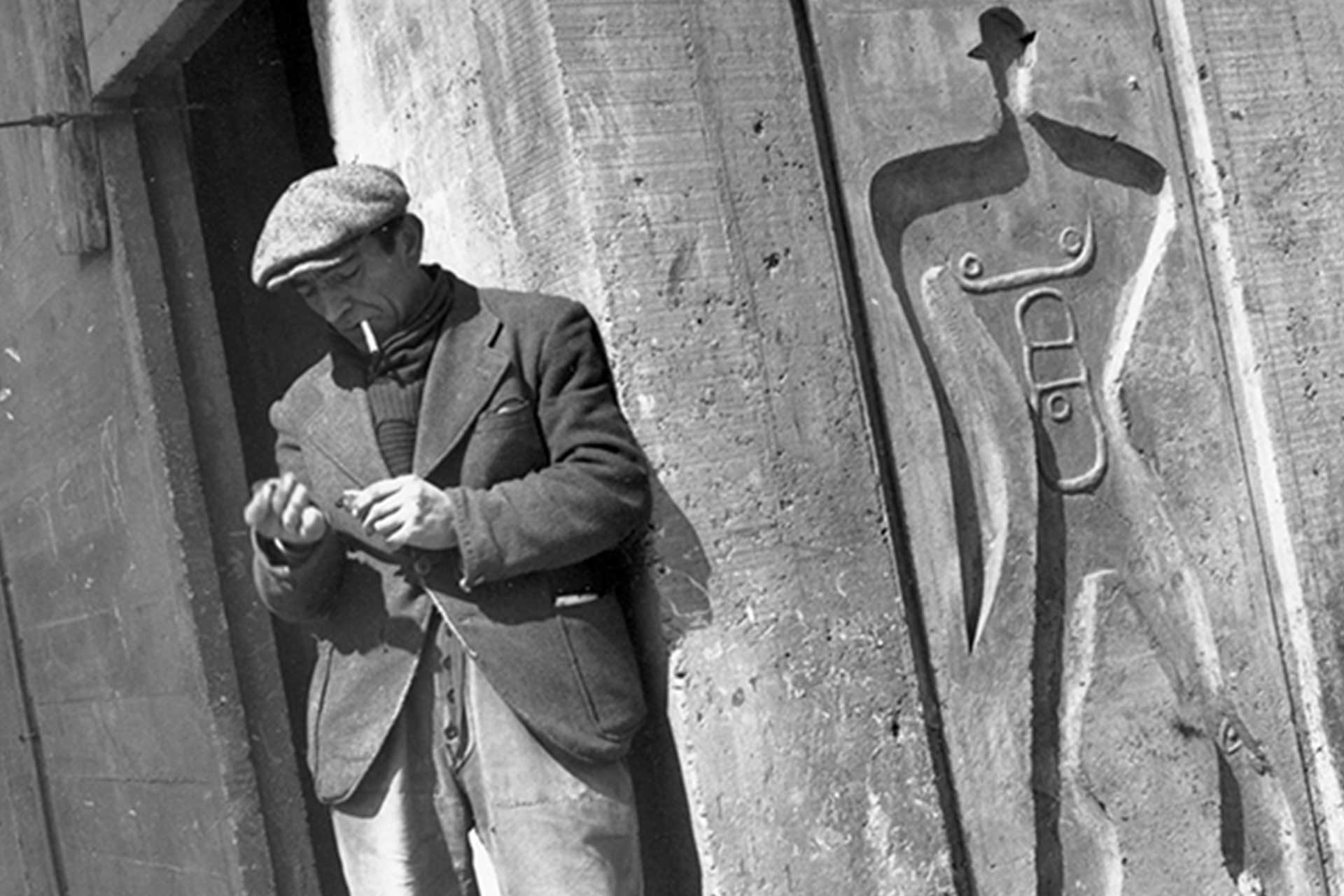

Le Corbusier Cabanon: the history

Three billion tons of waste generation: research indicates that concrete production, construction and demolition waste generation are some of the main contributors of constant carbon dioxide emission into the atmosphere. Contemporary architectural project Cabanon designed by London-based architect and artist, Nicolas Henninger, addresses the problem. Cabanon, eight feet by eight feet dwelling made of local and reclaimed wood in Leeds is a response to the belief that contemporary houses encourage wasteful ways of living and takes reference from Swiss-French architect designer, artist and writer Le Corbusier’s minimal retreat home in France.

Le Corbusier’s Cabanon, which he started building in 1951, took a design approach that was minimal but functional by combining the notion of minimum cell living with the concept of the primitive hut. The rise of ‘minimum dwelling’ began with the modernist work of Czech artist, writer, critic Karel Teige which introduced a form of domestic space that was split between individual cell and collective facilities. The potential of minimum dwelling as a form of living was further explored by Teige who wrote about the reduction of individual living space to address the rising modern plea for a ‘subsistence minimum’.

The concept of minimum dwelling

A combination of the ‘cell’ brought to the forefront by Teige and the occupancy of single huts by monastic communities was seen as the model for an ideal life as detailed in French literary theorist and essayist, Roland Barthes’ book How to Live Together, and became the heart of the work of twentieth century architects like Corbusier. Today, the concept of minimum dwelling is returning to cities like New York, London and San Francisco due to a housing crisis driven by the extreme commodification of houses and land. This new form of minimum dwelling, often referred to as a ‘microflat’, is an extreme reduction of the traditional housing, lacking both the affordability as well as the ethos of their historical precedent.

Amidst the pandemic in particular, many developed countries have seen house prices rise, with prices up by five percent in the US and eleven percent in Germany up eleven percent, according to Swiss banking giant, UBS. With about one-point-six billion people living in substandard housing and 100 million becoming homeless, as per United Nations’ statistics, traditional construction methods have been unable to keep up with the demand. Architectural projects like Cabanon which is made from sustainable timbre are energy efficient and could be a possible solution to both the housing and the environmental crisis.

Nicolas Henninger’s cabin in an urban environment

«The Cabanon encourages sustainability in two ways. First, the project is about reducing the scale of space you need. If a client wants to construct a 100 square meter house, prompt them to consider if they need that much space, can they fit everything they need in seventy square meters? Second, the cabin uses compostable materials like wood wool for insulation and reclaimed timber for the flooring which require less energy to be processed», says Henninger.

The cabin which has been set up in the back of the Arts Hotel in Leeds emulates the feel of being in a cabin in the woods but within the easy reach of a city setting, enabling visitors to experience low-waste living in an urban atmosphere and consider the material changes they can make in their lives. «The idea is going back into nature, away from the busy city life for a short retreat. It doesn’t have running water or a bathroom, but these things are already an existing facility of nature. You’re going back to the basics», explains Henninger.

Cabanon will also work in tandem with fellow artist Jake Krushell’s project Turbine, using a handmade mini wind turbine to power the cabin. The project which is also part of the ‘The Space Between’ program under East Street Arts’ Season for Change initiative is inspired by Hugh Piggott’s book The Wind Turbine Cookbook and addresses the intersection of sustainable art production and energy. Though the turbine is designed to work as a permanent energy source that will partly power the Cabanon, Henninger admits, that the cabin is off-the-grid for now as the turbine needs to be fitted into the roof of the cabin, so that it can harness the wind without being obstructed by the high-rise building that surrounds it.

Lampoon reporting: the high cost of sustainability

The use of alternatives like compressed wood fibers for insulation or wind turbines for power is more sustainable, but does it cost more? The simple answer is yes. «The cost of materials used is more expensive. The production of the insulation materials like rock wool is cheaper, but working with it is cumbersome. It’s hard to cut, what you’re exposed to and breathe in is toxic. On the other hand, sheep wool or wood wool is much friendlier to work with. But the price of purchasing it will be four times the price of the chemically-produced one», says Henninger.

There are four different types of wool insulation; sheep wool, glass wool, rock wool and hemp wool. Of the four, glass wool and rock wool are the cheaper options available for purchase at two pounds per square meter and five pounds per square meter respectively. On the other hand, sheep wool and hemp wool are the natural and breathable options. Due to relatively high demand these insulations are more costly at twenty pounds per square meter and fifty pounds per square meter. Another reason for the high cost, Henninger adds, is that the scale of companies producing alternatives is much smaller than the corporations producing the chemical-based insulation.

Budgeting is the key to sustenance

Sustainability is about weighing the options between what the use of alternative materials costs you and what it costs the environment. «The perception is that by using cheaper, processed raw materials, you would be cutting costs. The cost is somewhere else. It’s in the waste, that isn’t degradable. Because at the end of a building’s life, when you take it down, and you have all this non-biodegradable insulation – what can you do with it? It’s about considering the fact that less cost for you might mean more cost on the environment», explains Henninger. From an architect’s point-of-view, he adds that budgeting is the key to sustenance.

Breaking it down by what he means, Henninger says, «In sustainable projects such as these, the budget needs to be fifty-fifty. Spending half of the budget on purchase and transport of materials, and the other half on the construction. If you anticipate the cost of purchasing the materials then you work to minimize the cost of design by making it a small and simpler design, say seventy square meters instead of 100 square meters. The cost of materials can be further reduced if we try to reuse different bits from other projects as I’ve done with Cabanon. Using what we’ve got to make something new and functional».

The tiny house movement and the future of low-waste, minimalist living

Considering the popularity of the tiny house movement, which according to a Virginia Tech study had eighty people moving from a full-sized home to a tiny home and forty-five percent downsizing their living space to reduce energy consumption, the likelihood of urban cabins like Cabanon becoming more than a retreat lifestyle seems very high. Minimalistic living on a permanent basis may not be for everyone in Henninger’ view. Moving to a house that’s no more than 400 square feet and possibly as small as sixty square feet is a huge commitment, «It’s not for everyone. There will be people who see this as more than just a retreat lifestyle, but many others who prefer urban lifestyle. It may not be a widely accepted model», he says.

As an artist who has worked on various temporary installations, by taking over a piece of land to revamp it and open it up to the public, Henninger states that future projects like Cabanon could encourage people to adopt more environment-friendly living arrangements on a short-term and temporary basis. He says, «Spending a few days experiencing a more frugal way of life could enable people to understand that instead of opting for more space, you could have everything you need within a compact architecture. It would be smaller, but smarter and more sustainable, something more fit-for-purpose, just what you require to live».

Nicolas Henninger

Currently based in London, where he has been since 2009, Nicolas Henninger is an architect, designer and artist who set up his own design and build practice OFCA in 2013. Prior to this, between 2003 and 2013,he was a member of the art and architecture collective EXYZT.