Post-war, post-austerity, and post-conscription: the oil paintings, watercolors and photographs of Patrick Procktor testifying societal change in 1960s Britain

The Sixties in London

26 Manchester Street, Marylebone – a poignant address in London, a flat which saw the socialization and emancipation of the British art scene. A collection of artists, designers, singers and models, congregated for discussion, partying, painting and love-making. The West End address belonged to, and was the home of, artist Patrick Procktor. Together with David Hockney, they were part of a circle of creatives adding narrative to the so-called Swinging Sixties.

The decade became synonymous with political and social change: the austerity years of the Second World War were almost over, an era with painted black doors, food-rationing and minimal clothing. The Sixties emphasized a time for optimism and sexual revolution. The Baby Boom of the Fifties paired with the subsequent post-war economic growth signified that forty percent of the general population by the Sixties were under the age of twenty-five.

Mary Quant, the fashion designer of the Chelsea Set, opened her first Bazaar shop in 1955. She became renowned for her designs, including the mini-skirt and white lapels. On the radio, one would hear the likes of The Kinks, The Rolling Stones and The Beatles. In advertising and magazines, one saw the next generation of waif supermodels led by Jean Shrimpton and Twiggy.

The Pop Art movement

With the introduction of color supplements in newspapers, artists understood how the media played a key role in their promotion and for their works to reach the public and go further than the exclusive art clique. The Sunday Times launched the first color supplement in 1962 featuring a two-page spread on the artist Peter Blake. The Pop Art movement overtook the art scene, with artists experimenting in print, mass production and simplified color palettes.

Often regarded as an American export, many of the art movement’s origins came from Britain. The English artist Richard Hamilton wrote a letter in 1957 containing a list of words that characterized Pop Art. It read Popular (designed for a mass audience); Transient (short-term solution); Expendable (easily forgotten); Low-cost; Young; Witty; Sexy; Gimmicky; Glamorous; Big business. The art movement was simultaneously a celebration and a critique of popular culture and the mass media.

The Sixties in London oversaw a period of defining art schools and their departments. This included the Slade School of Fine Art, Central St Martin’s, Chelsea School of Art, Royal College of Art, Camberwell and so forth. Graduates and non-graduates were making bold decisions. The decade produced Bridget Riley, Eduardo Paolozzi, Patrick Caulfield, Allen Jones, Pauline Boty and others.

Dr. Ian Massey for Lampoon

In addition to these names, there is the aforementioned visual artist Patrick Procktor. «This is the generation whose childhood was spent in wartime, coming out the other side. The world started to open up, seeming like a world of new possibilities. Procktor was an integral member of his social circle, with Hockney, the fashion designer Ossie Clark and his wife the textile designer Celia Birtwell, Richard Beer, Peter Schlesinger, Mo McDermott, David Gwinnutt and even royalty, Princess Margaret. It was post-war Britain. The Swinging Sixties have almost become a cliché, almost mythologized» says Dr. Ian Massey, Patrick Procktor’s biographer.

Procktor was a born performer, prone to dressing as an eighteenth-century dandy, camp and theatrical

Patrick Procktor RA (1936-2003) was born in Dublin to English parents, and moved back to London as a child. His mother was unable to afford further education at university. As a result Procktor went to work from a young age. He joined the Royal Navy in 1954 to complete his National Service. He became fluent in Russian and accompanied several trade delegations as an interpreter.

Once finished, Procktor attended the Slade School of Fine Art from 1958 to 1962. His time at the Slade was fundamental in his formation as an artist and the development of his works in the following years. Whilst studying, he was witness to two teaching styles. «He came under the influence of mature students who had worked with the painter David Bomberg. The works were gestural, expressive and utilized thick impasto. Yet at the same time, there was another tendency which was the Euston Road School; this style was restrained, and measured in comparison. Procktor went for the former, in part due to the performative and physical making of the work, almost theatrical. He carried that style through».

Procktor was a born performer, prone to dressing as an eighteenth-century dandy, camp and theatrical. Simultaneously he was serious when it came to his artistic research, he was ambitious and an intellectual. As noted by Dr. Massey, in terms of how Procktor presented himself to both his friends and the public, «he was often self-deprecating, creating a smokescreen for his shyness, and to a certain degree his insecurity. This led to Procktor being misunderstood, misconstrued, and considered less serious than he actually was. He would immerse himself in the history of art, observing and learning in an analytical manner. To those excluded from the social circle, he had his defensive repartee, but behind the facade there was a ‘sombre’ person».

Procktor at the Redfern Gallery

By the time he had finished art school, «he was assimilating influences from David Bomberg, Francis Bacon, Graham Sutherland, Keith Vaughan, who taught him at the Slade, and all of whom carried through into his first exhibition at the Redfern Gallery in 1963, which was considered to be a success. He managed to have critics on his side, such as John Berger. There was press at the exhibition, who aided his reputation in the contemporary art scene».

The oil paintings shown at the Redfern Gallery revealed elongated and almost disfigured bodies, exaggerated features and a youthful confidence in color and technique. In the years to come, Procktor’s works were bought by collectors and public and private institutions, the Tate, the National Portrait Gallery, the Royal Academy and MoMA (NY), exhibited in group shows and even appearing on the cover art for Elton John’s 1976 album Blue Moves.

The Redfern Gallery now manages the artist’s estate. Procktor won the support of artist and teacher Keith Vaughan and The Whitechapel Gallery director, Bryan Robertson. Under Robertson’s direction from 1952 to 1969, The Whitechapel Gallery organized shows with pieces from American artists, such as Mark Rothko, Robert Rauschenberg and Franz Kline. One year on from Procktor’s debut at the Redfern Gallery, Robertson invited him to participate in an exhibition dedicated to twelve young painters titled The New Generation, 1964.

The New Generation, 1964

Procktor became a skilled watercolorist. «In the summer of 1967, he took up watercolors. He was on holiday in Europe with Hockney and Hockney’s then boyfriend, Peter Schlesinger. Hockney had with him a set of watercolors and, frustrated with the medium, decided to give them to Procktor. Procktor demonstrated a natural empathy, having already used them in the past in combination with other media, however now he was developing the skill to use watercolor on its own; he began to paint portraits, landscapes, still life».

The artist experimented with landscapes, motivated by his travels to mainland Europe, India, China and Egypt.The modest artist’s philosophy was reflected in Oscar Wilde’s preface to A Picture of Dorian Gray: «To reveal art and conceal the artist, is art’s aim». Procktor’s artworks testify to the revolutionary period of time in which Procktor was both living and producing art.

The Sexual Offences Bill

The artist chose to explore themes influenced by societal change and his growing bohemian circle. A prominent theme within his works centers on his sexuality and his relationships, whether as friends or lovers, with other men. Procktor was a gay artist in a country whose government did not legalize homosexuality until 1967.

Prior to the introduction of the Sexual Offences Bill, members of the LGBTQ+ community in England risked imprisonment and chemical castration. A United Kingdom opinion poll conducted in 1965 found that 93% of the respondents saw homosexuality as a form of illness requiring medical treatment.

«Several of Procktor’s early paintings are encoded with messages, which only the initiated would understand, those being the members of his close circle. There are allusions to his relationship with the Whitechapel Gallery director Bryan Robertson and to his relationship to the artist Michael Upton. In this group of friends, most of the men were gay and there were very few women, apart from Celia Birtwell. Having grown up through the war years, they reinvented the Bright Young Things of the 1920s and 1930s. Inspired by artists and socialites, Cecil Beaton, Stephen Tennant and Rex Whistler, they became the new golden youth of the Sixties. Procktor was surrounded by a talented group of people, creating mutual support for each other, in their professional and personal lives».

Patrick Procktor’s artistic research: the National Portrait Gallery

Within his artistic research Procktor played with the fine line between reality and fiction, the former represented by his friends and lovers, the latter by his use of iconography, a key theme in the Pop Art movement. Among his works, Procktor incorporated iconic figures of the decade, from the celebrity to the political. He transformed photographs found in newspapers and in popular culture of famous musicians dressed in drag and leather boys into figurative works.

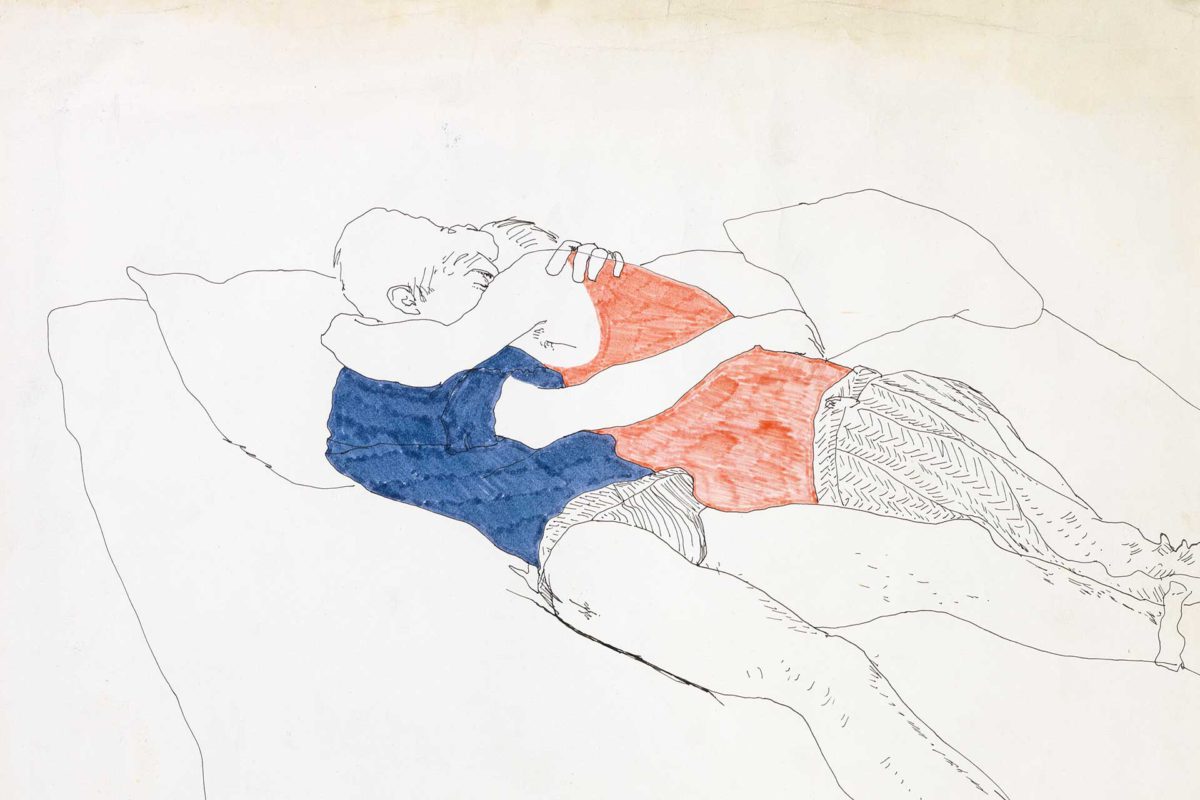

Each person is a symbol of change within the period, from a growing acceptance of non-conformist views and openness towards homosexuality to Britain’s involvement in international affairs. As Procktor’s social circle continued to grow, he was invited and commissioned to paint various members of the creative scene in London. In 1967 the Royal Court Theatre commissioned a portrait of the playwright Joe Orton. The final image is an ink line drawing of Orton reclining on a bed completely nude, apart from a pair of socks.

The drawing was later acquired by the National Portrait Gallery. A further example of Procktor’s connections and his love for the theater was an oil painting of actor Jill Bennett in 1972. In addition to portraiture, Procktor partly dedicated his work to the world of theater, unable to perform perhaps due to his 6 foot 5 frame, this was a means for Procktor to stay connected to the stage. His first commission was to design a mural for a John Whiting play at the Theatre Royal in Stratford in 1965 and in the following period other commissions ensued including a design for a Christopher Hampton play at the Royal Court Theatre.

The next muse and love Gervase Griffiths

In 1968, Procktor met his next muse and love Gervase Griffiths, a twenty-two year old model and aspiring singer. The Mick Jagger look-alike was asked to pose for a piece at Procktor’s home-studio after they met at a fashion show in the spring. The artist and muse blurred the lines of their liaison and they merged into two lovers, a relationship that lasted two years.

«Griffiths came to live at Manchester Street, and for the rest of that year was the subject of an outpouring of drawings and paintings. Procktor photographed him ad infinitum on their various travels together, and many of these photographs were the sources for paintings». The relationship between the two men did not last, and in 1970 Procktor began a romantic relationship with his widowed neighbor and friend Kirsten Benson, who was already a mother to two young children.

The couple decided to wed three years later, when she became pregnant with their only child together, Nicholas. «Like gay men before and after him, there was the societal pressure, even a temptation to conform to convention», such as marriage. Benson can be seen as the subject in several works, in which Procktor has painted her portrait with oils in a soft, gentle manner.

26 Manchester Street was no more

«Procktor and Hockney were close friends for a long time, easily thought of in the same breath. Products of the early Sixties and considered to be artists of equal promise by the time they left art school. Hockney was working class from a Yorkshire family, whereas Procktor derived from a middle-class background».

The two artists were close in the beginning of their respective careers and they subsequently proceeded on their own paths. Hockney gained acclaim starting with his representation by Kasmin Gallery, his Pop Art color palette and his new social circle in America.

Procktor, on the other hand, did continue with his art, he was even elected to the Royal Academy in 1996, however the last decade of his life was afflicted with tragedy, death and alcoholism. In 1981, Procktor came to hear of his former lover’s death; Griffiths had accidentally drowned in the sea a few days after celebrating his thirty-sixth birthday. Three years later, Procktor’s wife suffered a heart attack and passed away at the age of forty-four.

The artist was left to self-medicate with alcohol and cigarettes, with two significant figures no longer in his life. Another death of sorts was a fire in Procktor’s Marylebone flat, his home for the past thirty-six years, which became uninhabitable. The blaze destroyed a number of artworks and rendered impossible the salvage of the artist’s four-decade archive. 26 Manchester Street was no more, its end was symbolic of Procktor’s glory in the years prior, where the flat had been the central hub of the Sixties London art scene. In the autumn following the fire, Procktor found himself charged with attempted murder after a confrontation with his mother, Barbara Procktor, and spent a month in HMP Woodhill prison until his mother decided to drop the charges.

The artist found himself without a home and a studio. He continued nonetheless to produce artworks even up to his death in August 2003. A blood clot had reached his lungs. Procktor’s pieces began to resemble his early works made during the Sixties. «Towards the end of his life, the late oils painted in the 1990s were more gestural, earthier and raw».

Patrick Procktor and Ian Massey

Due to Procktor’s early success on the contemporary art scene, fresh from art school and its teachings, he had felt that he was yet to find himself artistically. By his sixties, he had come full circle, having researched and experimented with various mediums and styles over the years, investigating the artist within, he came back to the Bombergesque paintings and the style which propelled his reputation in the early Sixties.

Patrick Procktor’s name has come to light in recent years thanks to the research and writing of the monograph by Dr. Massey published in 2010. Prior to Dr. Massey’s monograph, there was little in regard to concrete information on Procktor’s career, apart from a slim monograph written in 1997 by Procktor’s friend and art critic, John McEwen.

Previously, Procktor’s persona had been included in two films: A Bigger Splash (1973) recounting Hockney’s break up with Peter Schlesinger and his social circle, and Prick up your Ears (1987), the story of the relationship between playwright Joe Orton and actor Kenneth Halliwell. Dr. Massey had already been made aware of Procktor’s existence, yet on coming across a collection of his works at the Redfern Gallery in 2005, Dr. Massey felt inclined that there was more research to be done on the artist’s career. He interviewed over fifty people, travelled to numerous destinations and combed through years of archives to ensure that the information and dialogue surrounding Procktor was not only correct and up to date, but included in the historical narrative.

Procktor is a prime example of a British artist who began his career in Sixties London. He continued to testify to his surroundings through his art. Alongside literary works, the art market is another means of highlighting certain names in art history and is a clear measurement of an artist’s commercial success. In 2016, a Gervase inspired painting by Procktor went to auction at Christie’s London. It fetched up to £40,000 against an initial sale estimate of £10,000 – £15,000, establishing a new sale record for the English artist.

As soon as we die, we enter into fiction

Dr. Massey considers that, «Procktor’s post-humous reputation is contingent on the work I have done, and the reputation I consequently have made». Dr. Massey quotes the English writer Dame Hilary Mantel from The Reith Lectures: «As soon as we die, we enter into fiction. Once we can no longer speak for ourselves, we are interpreted. When we remember, we don’t reproduce the past, we create it». With each passing year, there are fewer witnesses and active participants of the Swinging Sixties.

Those who wish to understand the art scene, its relevance to societal change and its bohemian culture are reliant on existing historical narratives and stories passed on from those present. Dr. Massey’s detailed research into the life and career of one artist demonstrates the possibility of a utopian, or romantic, method in the continued formation and writing of art history. Principle figures remain significant due to their contribution to the art world, yet the countless other creatives, often placed to one side and given less thought, are not to be excluded. Artists require their peers, the happenings of their generation, not to build and live within an echo chamber but rather to encourage an environment where the artist can reveal himself and the art is a by-product.

Studying Procktor

Dr. Ian Massey is an independent art historian, writer and curator based in the UK. His publications include the monograph biography Patrick Procktor: Art and Life (Unicorn Press, 2010) and he is the co-author with Anthony Hepworth of Keith Vaughan: The Mature Oils (Sansom & Company, 2012). In 2012 Dr. Massey curated the first major retrospective of the work of Patrick Procktor since the artist’s death at Huddersfield Art Gallery.